Lifestyle Interventions May Fend Off Decline; Social Contact Helps

Quick Links

Part 1 of 2

Intuitively, we all know that a life of movement, social connection, and a nutritious diet is good for us. But can lifestyle and behavioral interventions really stave off dementia in people whose cognition has already started to slide? While a definitive answer remains hard to come by for these types of studies, findings presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, held July 31-August 4 in San Diego, favor a “yes.”

- “Maintain your Brain” study reported a boost from digital coaching.

- In the EXERT trial, people with MCI who exercised remained cognitively stable over a year.

- Small SUPERBRAIN-AD study suggests benefit from multimodal intervention.

A network of multimodal intervention studies is in full swing around the globe, with some reporting promising findings at the meeting. The Australian “Maintain Your Brain” study, which delivers digital personalized coaching in physical activity, diet, and brain health, boosted cognition in its participants over three years. In EXERT, a large Phase 3 trial that compared light versus moderate exercise in people with MCI, cognition held stable in both groups over a year. The study lacked a control group, but a matched group of participants from ADNI declined in that same amount of time, suggesting that both interventions may have done some good. A small South Korean study called SUPERBRAIN-AD also reported promising findings from its suite of lifestyle interventions among cognitively impaired people with amyloid plaques. Together, the findings suggest that participants respond well to both in-person and virtual formats of intervention, and that social contact and support, even when delivered remotely, plays a hand in the benefits.

Multimodal Intervention at Work Around the Globe

“Maintain Your Brain” and SUPERBRAIN-AD are part of the World Wide FINGERS network, a set of multimodal intervention trials. Each tailored to local culture and needs, the network started up around the globe in response to the success of the original FINGER trial, aka Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (Aug 2017 news; Rosenberg et al., 2020). The poster child of lifestyle modification studies, FINGER had boosted cognition and fended off chronic disease among participants in its intervention group (Jul 2014 conference news; Nov 2015 news; Marengoni et al., 2018).

At AAIC, scientists showed progress updates on six World Wide FINGERS network studies. Four are ongoing, hence had no outcome data to report. They are U.S. POINTER, MIND-China, the Latin American Fingers Initiative, and MET-FINGER—a version of FINGER with the drug metformin added in. Two of the studies had outcomes to report, and they were positive.

Maintain Your Brain (MYB) was one such study. It tested the cognitive effect of coached, multimodal interventions delivered entirely via a digital platform. Henry Brodaty of the Center for Healthy Brain Aging at the University of New South Wales in Sydney presented the primary outcome findings. Participants were recruited to MYB from the 45 and Up Study, Australia’s largest ongoing cohort study that includes some 250,000 participants, representing about 10 percent of the population of New South Wales (Bleicher et al., 2022). Initiated in 2005 to inform researchers and policy-makers about ways to improve health among an aging Australian population, the study tracks multiple factors related to healthy aging, including cardiovascular health, disabilities, social connections, housing and economic status, hospital visits, and medication use, to name a few. MYB recruited dementia-free, 55- to 77-year-olds from this cohort, who had at least two risk factors for dementia.

In the first year of the three-year trial, all participants received four 10-week modules to help them achieve healthy lifestyle changes such as physical activity, a Mediterranean diet, brain training exercises, and an online training program to reduce stress, anxiety, and depression. The experimental group received coaching for each of these modules. The coaching was personalized to each participant’s risk profile at baseline. The control group received static information for each module, based on publicly available Australian health guidelines.

For the next two years of the trial, participants received “booster sessions” for each module—once monthly for the coached group and once every quarter for the control group—to motivate them to keep up the healthy habits they’d learned. The researchers invited 96,418 participants to join the MYB study; 6,236 were ultimately enrolled and randomized equally to coaching versus control groups. Fewer than half—2,959 participants—completed the cognitive assessment at baseline and annually for all three years of the trial.

How did they do? The MYB’s primary outcome was change on a cognitive composite measured online with tests from COGSTATE and Cambridge Brain Science. On this composite, which included tests of visual memory, executive function, processing speed, and working memory, the coached group significantly outperformed the control group at years 1, 2, and 3.With its effect size of 0.1, the intervention was equivalent to delaying decline by one year, Brodaty said. For comparison, the effect size of the primary outcome for the FINGER trial was 0.04 over two years, he added.

“This was fresh data that none of us had seen before,” said Maria Carrillo of the Alzheimer’s Association following Brodaty’s talk.

Miia Kivipelto, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, who had led the FINGER trial, was happy to see data suggesting that a digital intervention was effective. However, she noted that in FINGER, the social, in-person component of the intervention seemed crucial to the trial’s success.

“MYB trial results are impressive,” agreed Hiroko Dodge of Oregon Health and Science University in Portland. She told Alzforum that while the trial did not target socialization per se, participants in the experimental group likely received plenty of social interaction through coaching, adding, “I assume that this social interaction component played some role in the shown efficacy and also helped maintain high adherence.”

Dodge herself headed the I-CONECT study, which also presented outcome findings at AAIC. That trial found that even minimal social contact, delivered via phone or video chat, may bolster cognition and feelings of social connectedness among people with MCI. For details on those findings, read Part 2 of this series.

Laura Baker of Wake Forest University School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, presented the topline results of the EXERT study, an exercise trial with social benefits. Coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS), EXERT tested how exercise affects cognition among sedentary people with MCI. Participants were randomized into two intervention groups. One involved moderate-intensity aerobic exercise; the other, stretching, balance, and range-of-motion exercises. Both groups exercised at local YMCA health centers, where they met with coaches who had been trained to work with people with MCI. Participants were prescribed a 30- to 40-minute session four times per week—twice with their trainers and twice on their own. During the supervised sessions, the trainers asked participants specific questions to gauge how well they had complied with their solo assignments.

EXERT had 148 participants each in the stretching/balance/range of motion (SBR) and the aerobic exercise groups. Of the total 296, 257 started the program and completed at least one cognitive evaluation; 229—114 in the SBR and 115 in the aerobic group—completed the 12-month trial.

Baker reported no significant difference between the groups on primary outcome, which was change from baseline on the ADAS-Cog-Exec, a cognitive composite tailored for the trial that emphasizes executive function. By this measure, the trial missed its primary endpoint.

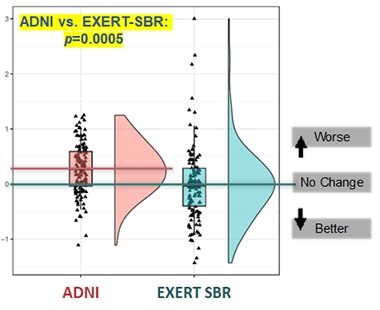

The researchers had anticipated this possibility, as neither intervention group was a control. To gauge how their participants’ cognitive trajectory might measure up to the natural course of decline, the researchers compared it to that of ADNI volunteers selected to match EXERT participants by age, sex, education, baseline cognitive status, and ApoE genotype. Baker reported that while these ADNI participants declined on the ADAS-Cog-Exec over 12 months, neither of the EXERT groups did. The difference between each EXERT intervention group and the matched ADNI group were statistically significant.

EXERTion Holds Off Decline? Cognition held stable for a year among participants in both EXERT intervention groups (stretching, balance, range of motion shown here); a closely matched group of ADNI participants slid in that time. [Courtesy of Laura Baker.]

Baker told Alzforum that in addition to remaining cognitively stable, EXERT participants maintained the size of their hippocampi throughout the study, whereas the hippocampus shrank over a year in the matched ADNI participants. Following the 12-month phase of supported exercise, participants were asked to continue their exercise routine on their own for six more months, and after that time underwent a final cognitive assessment. Those findings, along with blood biomarker measurements for Aβ, p-tau, and tau, will be presented at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease meeting in November, Baker said.

While the comparison to matched ADNI participants supports the idea that both interventions may have worked, it is not proof. Why didn’t EXERT include a typical control group? The answer comes down to right and wrong, and practicality. “It did not feel ethical to put people with MCI into a ‘do-nothing’ control group,” Baker said. She also feared that participants in such a control group might disproportionately drop out, realizing they were getting no benefit. Finally, Baker said that it was no easy task to recruit hundreds of people with MCI to participate in an exercise program four times per week for a year. “We had to do some selling,” Baker said. Guaranteeing that every participant would receive a bona fide intervention, including personal attention from a trainer, was a major draw for recruitment, Baker said.

Baker said that many of the participants developed meaningful relationships with their trainers, noting that during the COVID-19 pandemic, when gyms closed for a time and in-person sessions paused, many participants voiced concern about their trainers retaining their jobs. Many participants seemed hungry for social connection. When the whole study had to pause due to the pandemic, researchers called the participants every week to encourage them to continue their exercise at home. “Many said that this was the only phone call they got all week long,” Baker said.

If both groups did benefit, was it due to the exercise, to the social interactions with their trainer, or perhaps to the cognitive stimulation of leaving the house four times a week? Baker thinks it’s possible all of these factors contributed, although it’s difficult to tease them apart. In past studies in which people with MCI were given a trainer once per week and asked to exercise on their own three times per week, many only showed up for the sessions with the trainer. “I feel pretty confident that we would not see protection among people with MCI without support,” Baker said. “Unless there’s social engagement, they won’t do it.”

To Dodge, the finding that both intervention groups experienced the same cognitive stability suggests that factors besides physical exercise itself, such as socialization, might be playing an important role in the benefit. “Combining the recent I-CONECT results along with the findings of the EXERT trial suggests that enhancing socialization might be a good prevention strategy to delay cognitive decline,” Dodge said.

Besides EXERT, Baker also co-leads Protect through a Lifestyle Intervention to Reduce Risk (U.S. POINTER). This Phase 3 trial evaluates the combined power of physical and mental exercise, a healthful diet, and close management of cardiovascular health on cognition. The trial has enrolled about 1,600 participants out of a planned 2,000 so far, Baker told Alzforum, and results are expected in 2025.

In the meantime, Jeff Katula of Wake Forest updated AAIC attendees about how the COVID-19 pandemic, which emerged just months after the trial began, influenced design and adherence. The trial's interventions had been geared toward in-person meetings and exercise but, after a five-month hiatus at the start of the pandemic, the trial switched to an all-virtual format. It essentially yo-yoed back and forth between virtual and in-person formats as COVID-19 surges rose and fell. Participants weathered these changes remarkably well, adhering just as well to their regimens regardless of format, Katula reported. In fact, according to FitBit data, participants were slightly more active during virtual stints. In all, the findings suggest that even intensive, multimodal intervention studies can adapt to challenges like a global pandemic, and that participants are highly responsive to virtual communication, Katula concluded.

Finally, a small South Korean study posted promising results at AAIC. Eun Hye Lee of Ewha Womans University School of Medicine in Seoul presented findings from SUPERBRAIN-AD. This is an Alzheimer's-focused follow-up study to the previous SUPERBRAIN lifestyle intervention study (Park et al., 2020).

SUPERBRAIN-AD recruited 46 amyloid-PET-positive participants with MCI or mild dementia, and randomized them into three groups—two interventions and one control—for an eight-week trial. One intervention group received a suite of in-person lifestyle support, including help with managing metabolic and vascular risk factors, cognitive training and social activity, physical exercise, nutritional guidance, motivational enhancement, as well as a nutritional supplement drink. The second intervention group only received the nutritional supplement, a multivitamin drink with added ingredients purported to boost brain function, including omega-3 fatty acids, medium-chain triglycerides, phosphatidyl serine, and disodium 5' uridylate. The control group was put on a waitlist for future intervention, and received a booklet of lifestyle guidelines to prevent dementia.

The primary outcome was change in RBANS total score at eight weeks. Lee reported that participants in both the multimodal and supplement groups improved their scores over eight weeks, while the control group declined. The multimodal group improved substantially more than the supplement group. According to Lee, participants in the multimodal group also outperformed those in the other groups on secondary outcome measures, such as the Korean MMSE, and on exploratory measures including a boost in healthy bacterial species inhabiting the gut.—Jessica Shugart

References

News Citations

- New Dementia Trials to Test Lifestyle Interventions

- Healthy Lives, Healthy Minds: Is it Really True?

- Health Interventions Boost Cognition—But Do They Delay Dementia?

- A Chat Every Other Day Keeps Dementia at Bay?

Paper Citations

- Rosenberg A, Mangialasche F, Ngandu T, Solomon A, Kivipelto M. Multidomain Interventions to Prevent Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer's Disease, and Dementia: From FINGER to World-Wide FINGERS. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2020;7(1):29-36. PubMed.

- Marengoni A, Rizzuto D, Fratiglioni L, Antikainen R, Laatikainen T, Lehtisalo J, Peltonen M, Soininen H, Strandberg T, Tuomilehto J, Kivipelto M, Ngandu T. The Effect of a 2-Year Intervention Consisting of Diet, Physical Exercise, Cognitive Training, and Monitoring of Vascular Risk on Chronic Morbidity-the FINGER Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018 Apr;19(4):355-360.e1. Epub 2017 Nov 3 PubMed.

- Bleicher K, Summerhayes R, Baynes S, Swarbrick M, Navin Cristina T, Luc H, Dawson G, Cowle A, Dolja-Gore X, McNamara M. Cohort Profile Update: The 45 and Up Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2022 May 23; PubMed.

- Park HK, Jeong JH, Moon SY, Park YK, Hong CH, Na HR, Song HS, Lee SM, Choi M, Park KW, Kim BC, Cho SH, Chun BO, Choi SH. South Korean Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Protect Brain Health Through Lifestyle Intervention in At-Risk Elderly People: Protocol of a Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Feasibility Trial. J Clin Neurol. 2020 Apr;16(2):292-303. PubMed.

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.