Do 'Headers' Rack Up Brain Damage in Soccer Players?

Quick Links

NFL retirees may not be the only footballers at risk for chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Heading the ball may put players of the world’s most popular sport, soccer, at risk for the neurodegenerative condition as well, according to two recent studies. In the most detailed pathological study on CTE in soccer players to date, Janice Holton and Tamas Revesz at University College London found a high incidence of CTE in 14 former players who had developed dementia. As detailed in the February 15 Acta Neuropathologica, all these athletes had headed the ball thousands of times during their careers yet had, at most, one diagnosed concussion. The authors suggest that repeated sub-concussive impacts may have been causal in their disease. In a separate study, published online February 1 in Neurology, scientists led by Michael Lipton, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, found that in 222 young, active amateurs, heading the ball associated with concussion-like symptoms. Together, these studies hint at the dangers of heading at different points in a player’s career, Lipton told Alzforum. “Numerous repeated impacts that may not be recognized as concussion may add up to a problem down the road,” he said.

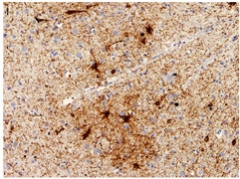

Clumps of Tau.

Patchy tau aggregates (brown) in neurons, astrocytes, and cell processes in the temporal cortex of a retired soccer player. [Courtesy of Ling/Acta Neuropathologica.]

CTE is a progressive degenerative disease that vitiates the brains of some boxers, American football players, hockey players, and soldiers, all of whom may experience severe concussions as part of their jobs (for a review, see McKee et al., 2016). Little is known about the condition in people who play soccer. The average player suffers but one or two concussions over a decades-long career, though they may endure numerous other accidental hits to the head, for instance by banging against another player, crashing to the ground, or thudding up against a goalpost. They also intentionally head the ball dozens of times a week, adding up to thousands of sub-concussive impacts over a career.

Could these repetitive hits to the head lead to CTE? Recent media attention has swirled around that question. The death in 2002 of 59-year-old former center forward and English international Jeff Astle was attributed to CTE, and four of the eight surviving members of the English team that won the 1966 World Cup now suffer from dementia. So far in the literature, only four case studies have reported brain damage in retired soccer players: Three of those people had CTE and one had Alzheimer’s pathology (McKee et al., 2014; Hales et al., 2014; Grinberg et al., 2016; Bieniek et al., 2015). No one had analyzed a group of players.

The project on retired soccer players got its start in the 1980s with co-author and psychiatrist David Williams, then of the psychiatric hospital at Cefn Coed, in Swansea, Wales. Williams treated a 58-year-old retired professional soccer player who had advanced dementia. As this patient had been a skilled header of the ball, Williams wondered if repetitive head impacts could explain his cognitive impairment and early disease onset. Williams and colleagues, including first authors Helen Ling and Huw Morris, followed this patient, as well as 12 other retired soccer players and one avid amateur referred to the clinic for progressive cognitive impairment, over the next 30 years. The researchers collected data on the patients and got information from caregivers on concussions, memory symptoms, and career history, and took clinical and demographic data from medical records.

All had started playing in childhood or adolescence. Six had experienced a single concussion in a game. Five of them had lost consciousness from the concussion. They all experienced cognitive impairment—the onset ranged from 40 to 78 years—that lasted about a decade. Each had one or more accompanying symptoms, such as motor impairment, hallucination, or behavioral changes. Twelve had a CT or magnetic resonance imaging scans soon after onset of their neurological symptoms, which revealed cortical atrophy.

Six brains were donated for postmortem analyses. All had TDP-43, Aβ, and tau pathology, with Lewy bodies in one case. Four had true CTE as defined by recent NINDS criteria, marked by tau aggregation in the neurons, astrocytes, and cell processes around blood vessels, particularly in the cortical sulci (McKee et al., 2016). Tau pathology turned up in other areas of the remaining two patients, and all had dilation of the third ventricle, features supportive of a CTE diagnosis.

All six postmortem patients also had holes in the septum pellucidum, a thin membrane in the middle of the brain that can tear in response to mechanical stress. “This is perhaps the most striking pathological finding of all,” wrote Simon Vann Jones, Franklyn Community Hospital, Exeter, U.K., to Alzforum. He was not involved in the study. Since damage to the septum is uncommon in the general population, and since these players had at most only one documented concussion, chronic low-level trauma was likely responsible for this rupture, he said. Vann Jones also noted that all six postmortem patients experienced significant personality changes soon after dementia diagnosis, suggesting such shifts may be a common clinical marker of CTE. However, the study yields no insight about how common CTE is in soccer players, he cautioned in an email (see full comment below). Even so, he found this a valuable study. “The findings raise an alarm for all sports and activities that involve low-level head trauma and should encourage further measures to mitigate this risk.”

Ling said the results fit with prior, larger studies that suggest head impacts without concussions are associated with CTE (Stein et al., 2015). The group is currently searching for biomarkers in blood, urine, or saliva that reflect brain trauma and predict CTE in athletes, she said.

“This is confirmation that CTE can occur in soccer players,” wrote Kaj Blennow, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, to Alzforum. He called for longitudinal studies on players of different contact sports to determine how frequently CTE occurs, which factors—such as concussion severity or length of career—contribute to its development, and which might protect from the condition.

“The paper fits perfectly with evidence that head injuries in football, hockey, and soccer are reasonably dangerous and could lead to CTE,” said Robert Friedland, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Kentucky. This also supports the emerging idea that multiple concussions are not necessary for brain damage to occur, he said.

Heading Symptoms Fly Under the Radar

Lipton’s study highlights the dangers amateur players may face when heading a soccer ball. He and first author Walter Stewart of Sutter Health Research in Walnut Creek, California, surveyed 222 active, amateur players aged 18 to 55 about how often in the past two weeks they had headed a ball versus how many times they had hit their heads against other players, the ground, or goalposts. Stewart and colleagues found that both intentional and unintentional hits to the head led to symptoms such as headache, dizziness, and nausea. Risk tripled in the quartile of players who headed the most, compared to those who reported no head impacts. Unintentional impacts had their own effect, with a single event tripling risk for symptoms and two or more leading to sixfold higher instance.

“The papers and guidelines in the literature suggest that heading is not a common cause of recognizable concussion,” Lipton told Alzforum. “We are challenging that by saying heading does cause concussive symptoms.” However, that’s not the biggest problem, he said. “The question is, what does repeatedly having your head impacted over years do to your brain? Precious little has been done to understand that.”

Recent research and lawsuits have led to a U.S. Youth Soccer ban on heading in players younger than 10, with limits imposed on those aged 11 or 12. Heading is unlikely to be eliminated from the game entirely, Lipton said, but more research into how much is tolerable to the brain and who is most susceptible to damage will help make the game safer for players. “As with many of the dangers we are exposed to, the evidence suggests that heading is not an all-or-nothing bad thing,” said Lipton. “Guidelines that prevent people from overdoing it are much more likely to gain traction than an absolute ban.”

Robert Stern, Boston University, agreed that a ban on heading wouldn’t be warranted based on this one paper, and added that he doesn’t think parents should prevent kids from playing, either. “We need to conduct a lot more research on how great an impact heading has first.” However, this study adds more evidence that repetitive sub-concussive trauma may lead to a neurodegenerative disease, he said.

In response to recent research, including these two papers, a spokesperson for FIFA, the word governing body of soccer, said, “To our best knowledge, there is currently no true evidence of the negative effect of heading or other sub-concussive blows. FIFA will continue to monitor the situation of head injuries, maintaining constant contact with current and ongoing studies regarding long-term neurocognitive changes, both in male and female football players. Protecting the health of football players is and will remain a top priority in developing the game.”—Gwyneth Dickey Zakaib

References

Paper Citations

- McKee AC, Alosco ML, Huber BR. Repetitive Head Impacts and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2016 Oct;27(4):529-35. PubMed.

- McKee AC, Daneshvar DH, Alvarez VE, Stein TD. The neuropathology of sport. Acta Neuropathol. 2014 Jan;127(1):29-51. Epub 2013 Dec 24 PubMed.

- Hales C, Neill S, Gearing M, Cooper D, Glass J, Lah J. Late-stage CTE pathology in a retired soccer player with dementia. Neurology. 2014 Dec 9;83(24):2307-9. Epub 2014 Nov 5 PubMed.

- Grinberg LT, Anghinah R, Nascimento CF, Amaro E, Leite RP, Martin Md, Naslavsky MS, Takada LT, Filho WJ, Pasqualucci CA, Nitrini R. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Presenting as Alzheimer's Disease in a Retired Soccer Player. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016 Jul 29;54(1):169-74. PubMed.

- Bieniek KF, Ross OA, Cormier KA, Walton RL, Soto-Ortolaza A, Johnston AE, DeSaro P, Boylan KB, Graff-Radford NR, Wszolek ZK, Rademakers R, Boeve BF, McKee AC, Dickson DW. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy pathology in a neurodegenerative disorders brain bank. Acta Neuropathol. 2015 Dec;130(6):877-89. Epub 2015 Oct 30 PubMed.

- McKee AC, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Folkerth RD, Keene CD, Litvan I, Perl DP, Stein TD, Vonsattel JP, Stewart W, Tripodis Y, Crary JF, Bieniek KF, Dams-O'Connor K, Alvarez VE, Gordon WA, TBI/CTE group. The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2016 Jan;131(1):75-86. Epub 2015 Dec 14 PubMed.

- Stein TD, Alvarez VE, McKee AC. Concussion in Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2015 Oct;19(10):47. PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Papa L, Ramia MM, Edwards D, Johnson BD, Slobounov SM. Systematic review of clinical studies examining biomarkers of brain injury in athletes after sports-related concussion. J Neurotrauma. 2015 May 15;32(10):661-73. Epub 2015 Jan 23 PubMed.

- Pullman MY, Dickstein DL, DeKosky ST, Gandy S. Antemortem biomarker support for a diagnosis of clinically probable chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Mol Psychiatry. 2017 Jan 10; PubMed.

- Woerman AL, Aoyagi A, Patel S, Kazmi SA, Lobach I, Grinberg LT, McKee AC, Seeley WW, Olson SH, Prusiner SB. Tau prions from Alzheimer's disease and chronic traumatic encephalopathy patients propagate in cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Dec 13;113(50):E8187-E8196. Epub 2016 Nov 28 PubMed.

- Lipton ML, Kim N, Zimmerman ME, Kim M, Stewart WF, Branch CA, Lipton RB. Soccer heading is associated with white matter microstructural and cognitive abnormalities. Radiology. 2013 Sep;268(3):850-7. Epub 2013 Jun 11 PubMed.

- Di Virgilio TG, Hunter A, Wilson L, Stewart W, Goodall S, Howatson G, Donaldson DI, Ietswaart M. Evidence for Acute Electrophysiological and Cognitive Changes Following Routine Soccer Heading. EBioMedicine. 2016 Nov;13:66-71. Epub 2016 Oct 23 PubMed.

- Khan K. Heading for trouble: is dementia a game changer for football?. BJSM Blog, 15 Feb 2017

News

- In NFL Players, Brain Inflammation May Persist Years After Head Trauma

- Axon Damage May Hinder Recovery from Concussion, Spark Neurodegeneration

- Vigorous Exercise: Could it Promote ALS in Women?

- Cognitive Decline in Young Football Player Tied to Extensive Brain Damage

- Large Grant for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Biomarker Study

Primary Papers

- Ling H, Morris HR, Neal JW, Lees AJ, Hardy J, Holton JL, Revesz T, Williams DD. Mixed pathologies including chronic traumatic encephalopathy account for dementia in retired association football (soccer) players. Acta Neuropathol. 2017 Mar;133(3):337-352. Epub 2017 Feb 15 PubMed.

- Stewart WF, Kim N, Ifrah CS, Lipton RB, Bachrach TA, Zimmerman ME, Kim M, Lipton ML. Symptoms from repeated intentional and unintentional head impact in soccer players. Neurology. 2017 Feb 1; PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

Boston University School of Medicine

This is an important clinicopathological case study involving a small cohort of demented subjects who were exposed to repetitive head impacts (RHI) through soccer participation for a prolonged period of time (average 26 years). The report greatly enhances the existing literature, as it is the largest postmortem series of soccer players ever reported. There are also several clinical and pathological features that are worth highlighting. First, all six players were initially diagnosed clinically and pathologically as having Alzheimer’s disease (AD), although the pathological diagnosis was changed to include CTE in four of the six after reexamination. This indicates that there is a critical need to go back and re-evaluate existing brain bank series for the presence of CTE using the recently defined NINDS criteria (McKee et al., 2016). Although this has been done by several groups (Bieniek et al., 2015; Ling et al., 2015; and Noy et al., 2016), the current study further emphasizes that CTE can masquerade as AD, pathologically and clinically, and is likely contaminating clinical trials and basic research studies in AD.

Another notable feature is that the soccer players with CTE had only one documented concussion, highlighting again that CTE is associated with prolonged exposure to mild RHI that are frequently clinically silent and do not rise to the level of a symptomatic concussion.

In addition, all six players had evidence of AD and previous traumatic injury (fenestrations of the septum pellucidum and one with cavum septum), including the two that did not meet NINDS criteria for CTE. This raises the question of whether prolonged exposure to RHI also accelerates or enhances the development of AD. Recently, the late-life effects of single traumatic brain injury (TBI) with loss of consciousness (LOC) were analyzed in 7,130 subjects from three large participant studies and found that TBI with LOC was not associated with cognitive impairment, dementia, clinical AD, or AD neuropathology, but was associated with Parkinson’s disease, parkinsonism, Lewy bodies and microinfarcts (Crane et al., 2016). Although this study suggests that single TBI with LOC is not associated with AD, it does not provide insight into the role of RHI in AD or how the co-existence of CTE might modify that relationship. Future studies are needed to evaluate how exposure to RHI and the presence of CTE impact the development of AD.

References:

McKee AC, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Folkerth RD, Keene CD, Litvan I, Perl DP, Stein TD, Vonsattel JP, Stewart W, Tripodis Y, Crary JF, Bieniek KF, Dams-O'Connor K, Alvarez VE, Gordon WA, TBI/CTE group. The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2016 Jan;131(1):75-86. Epub 2015 Dec 14 PubMed.

Bieniek KF, Ross OA, Cormier KA, Walton RL, Soto-Ortolaza A, Johnston AE, DeSaro P, Boylan KB, Graff-Radford NR, Wszolek ZK, Rademakers R, Boeve BF, McKee AC, Dickson DW. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy pathology in a neurodegenerative disorders brain bank. Acta Neuropathol. 2015 Dec;130(6):877-89. Epub 2015 Oct 30 PubMed.

Ling H, Holton JL, Shaw K, Davey K, Lashley T, Revesz T. Histological evidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a large series of neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 2015 Dec;130(6):891-3. Epub 2015 Oct 24 PubMed.

Noy S, Krawitz S, Del Bigio MR. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy-Like Abnormalities in a Routine Neuropathology Service. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2016 Nov 4; PubMed.

Crane PK, Gibbons LE, Dams-O'Connor K, Trittschuh E, Leverenz JB, Keene CD, Sonnen J, Montine TJ, Bennett DA, Leurgans S, Schneider JA, Larson EB. Association of Traumatic Brain Injury With Late-Life Neurodegenerative Conditions and Neuropathologic Findings. JAMA Neurol. 2016 Sep 1;73(9):1062-9. PubMed.

Franklyn Hospital

This is an important and valuable addition to the literature on the potential link between chronic, repetitive head injury (with heading in football being used as the model) and the risk of the later development of chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

Despite the limitations of the study—namely no control group and no denominator (the study recruited consecutive ex-footballers who attended a memory clinic in one region over 30 years. We are left to speculate as to how many footballers did not experience memory decline or how many did not have their past sporting history explored in clinic)—the extent of the findings, particularly at postmortem, make this a very valuable study.

Of the six players who underwent a postmortem, four had confirmed CTE and two had changes suggestive of CTE. The 100 percent prevalence of septal fenestration is perhaps the most striking pathological finding of all. It suggests that chronic low-level trauma was responsible for this change, particularly if the self-reported low prevalence of concussive injury in this group is accurate. The background population prevalence of just 6 percent makes this finding even more striking. Additionally, only six of the 14 participants reported a concussion during their career, however, retrospective accounts of head injury particularly are prone to recall bias and should be interpreted with caution.

It is also worth noting that all six patients who underwent postmortem had experienced significant personality changes as an early clinical feature, typically an increase in aggression. This supports previous studies in boxers and American football players and suggests that this may be a robust clinical biomarker of CTE. Another noteworthy clinical finding is the age of onset, with five of the 14 participants presenting with symptoms under the age of 60. This may reflect a more extensive exploration of past history (including sporting history) in patients who present young, and I am cautious about over-interpretation without knowing how many people in the population were also exposed to similar levels of chronic low-level head trauma. Nevertheless, these were unusually young patients experiencing significant clinical problems and the pathological findings support the likelihood that heading a football may have contributed to their early presentation.

The study does not address what factors place footballers at additional risk or those that may be protective. For every Jeff Astle there may be a Stanley Matthews, who died at 85 cognitively intact. The study acknowledges the desirability of having background genetic information—particularly ApoE E4 status—in these studies and also the difficulty of knowing the threshold for causing damage as well as mentioning that the change in a football design and weight may or may not have changed the level of risk. All 14 participants had used the old, 480g football at some point in their career.

The authors call for larger, prospective studies using a variety of imaging and other investigative techniques and certainly this would be desirable. However, I would like to see more made of the changes in personality in ex-players if this is indeed an early clinical biomarker for CTE. The alternative is to conduct an “ideal” prospective study of current players with accurate measures of trauma exposure and prospective follow-up. The results of such a study may not be conclusive for decades.

Regardless of the limitations of this study, the findings raise an alarm for all sports and activities that involve low-level head trauma and should encourage further measures to mitigate this risk.

Emory University School of Medicine

This study by Ling et al. increases the number of football (soccer) cases in the literature with some element of CTE pathology. Although the numbers still remain small, the authors indicate that four of six cases with CTE pathology is a much higher percentage than what may be expected in an elderly population, thereby supporting the hypothesis that CTE pathology in football players may be related to the prior history of heading the ball and/or player collisions. Having two of the six without CTE pathology is also an interesting finding because it suggests that some individuals may be more susceptible or resilient to forming CTE pathology than others. As with most of the prior football (soccer) CTE cases, the research subjects in the study had mixed pathologies (AD, TDP43, CTE), and this supports the concept of possible synergy with the aging process and/or other neurodegenerative diseases.

Overall, the authors point out limitations to the study, including small size and lack of some other detailed metrics, however, they also suggest that the prospective accumulation of histories and regular outpatient surveillance reduced selection and recall bias. Larger longitudinal prospective studies on football (soccer) players are needed to understand the scope of CTE pathology and traumatic encephalopathy syndrome in this patient population. We are hopeful that novel biomarkers (CSF, PET imaging, etc) will soon assist with diagnosis and also provide much-needed insight into how pathology/biomarkers may correlate with clinical symptoms.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.