Can Pencil-and-Paper Test Predict Pathology Behind PPA?

Quick Links

In the May 16 JAMA Neurology online, scientists led by Sandra Weintraub, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, report that a simple memory test developed in her lab can help tell the difference between primary progressive aphasia (PPA) due to two different protein pathologies—and distinguish both from amnestic dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Weintraub and her colleagues found that performance on the Three Word Three Shape (3W3S) test identified people who had pathologically confirmed PPA due to frontotemporal lobar degeneration, or atypical AD pathology. The test also distinguished PPA from typical AD. “The Three Word Three Shape test looks like a nice clinical tool that is simple and relatively short, and it should be more widely used,” wrote John Hodges, University of New South Wales, Sydney, in an accompanying editorial.

PPA is a progressive disorder that gnaws at a person’s ability to speak, read, or write. It results from neurodegeneration in areas of the brain that control speech and language. The disease can manifest in different ways, depending on which regions of the brain are hit hardest. People with the agrammatic form of PPA have trouble putting words together in the right order. Those with the logopenic form struggle to find the right word, and instead utter simpler substitutes or talk around it (for instance, saying “the thing you use to hit nails” because they can’t think of the word “hammer”).

Different proteopathies in the brain can lead to PPA. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD)—a family of diseases that cause atrophy in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain—underlies 60 to 70 percent of cases, and can be caused by either a buildup of abnormal forms of TDP-43 or tau. The structure and distribution of these tau accumulations differ from the tangles found in AD. The other 30 to 40 percent of patients have AD pathology, including Aβ plaques and tau tangles, in language centers of the brain. The agrammatic variant of PPA is often associated with FTLD-tau, while the logopenic form often involves AD. However, both pathologies can cause either type of disease. Amyloid scans and experimental tau imaging that might distinguish the two are expensive and not yet widely available.

Can a simple pencil-and-paper test suffice? According to first author Stephanie Kielb, the 3W3S test may be just the ticket (Weintraub et al., 2000). It was designed more than a decade ago to give a simple readout of episodic memory. Episodic memory remains mostly intact in PPA, but some patients have subtle deficits. Could those relate to specific pathology? “We wanted to see if there were patterns in performance that could help us distinguish between Alzheimer’s pathology and FTLD,” said Weintraub.

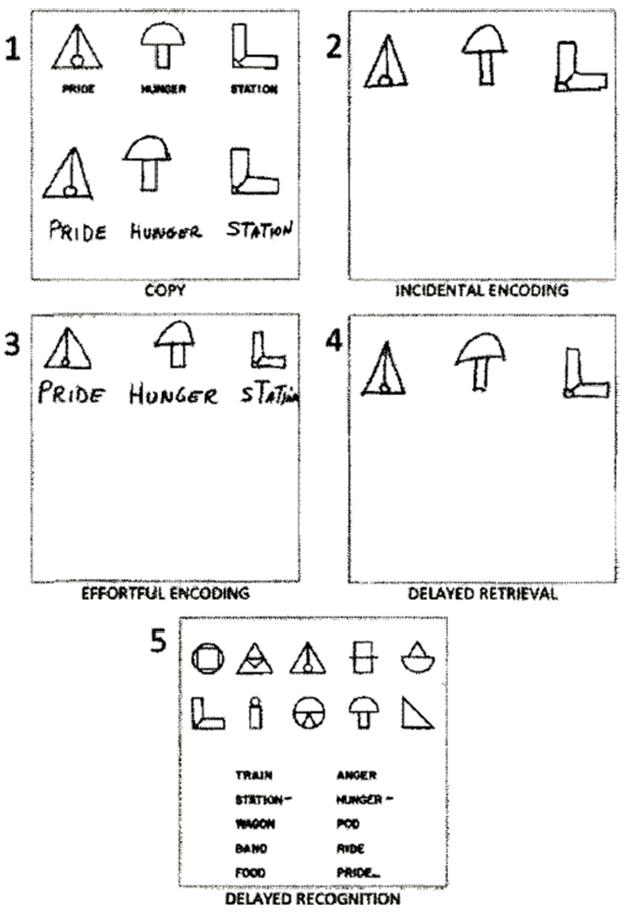

3W3S test. Participants are asked to copy (1), recall (2), study and reproduce (3), remember after a delay (4), and recognize (5) three shapes and associated text. Pictured is the typical performance of a PPA patient, who has trouble recalling words (as in 2 and 4) but not shapes. [Courtesy of Weintraub et al., 2013.]

The 3W3S test stands apart from other memory tests in that it requires minimal instruction. That helps patients with PPA; they often perform poorly in memory tests because they struggle to understand language-heavy directions. In a previous study, Weintraub and colleagues used the 3W3S test to separate clinically-diagnosed PPA patients who had trouble remembering only words, from AD patients whose deficits extended to non-verbal memories, such as recall of geometric shapes (Weintraub et al., 2013).

In the 3W3S test, a person copies drawings of three geometric shapes, each with a random word, such as “train” or “anger,” printed below it. They are not told they’ll need to remember these items, but later researchers ask them to redraw the same designs and words from memory. This subterfuge means the scientists are measuring “effortless learning,” since it relies on what subjects remember when they weren’t trying to learn. Next, they are asked to remember the same three shapes and words and get 30 seconds before they again draw from memory. Since this time they know ahead of time that they will need to reproduce the images, this measures “effortful learning.” They do this step three times. To test delayed recall, they draw the same shapes and words about 10 minutes later. Lastly, they pick out the shapes and words they previously saw from among 20 options.

This test was given to 19 dementia patients about seven years before they died, and their brains were later examined at autopsy. Six people were confirmed to have FTLD-tau pathology; all six had been diagnosed with the agrammatic variant of PPA. Seven had AD pathology in the language centers of their brains; six of them had been diagnosed with logopenic PPA and one with the agrammatic form. Six more had AD pathology in typical AD areas and had been diagnosed with amnestic AD dementia.

As Kielb and colleagues hypothesized, performance patterns on the 3W3S test distinguished these patients. Patients with underlying FTLD-tau performed as well as healthy elderly controls, showing only slight slip-ups in the “effortless learning” of words and shapes. Both the PPA-AD and amnestic AD groups made more mistakes in effortless learning, especially in recalling words. They also struggled with delayed recall, especially after the 10-minute delay (see image above for an example of typical PPA performance). Those with AD dementia exhibited all of these deficits, plus they couldn’t recall shapes in effortless learning or identify the three previously seen words and shapes from the 20-item list.

Why might these groups differ? In PPA due to FTLD-tau, brain regions involved in memory are relatively spared, so these patients have little trouble remembering words and shapes. In PPA-AD, some AD pathology invades the limbic portions of the brain, which participate in memory processes, and could explain subtle deficits. The same pathology heavily invades medial temporal regions—crucial for memory—in amnestic AD patients, which would account for the more severe nonverbal and recognition deficits.

Hodges pointed out that the impairments in PPA-AD patients could also be explained by trouble encoding verbal information. Alternatively, since the scoring depends in part on spelling words correctly, Aaron Meyer, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., suggested that PPA-AD patients might remember words but just can’t spell well. “Seeing the types of errors these patients are making would give more specific information about what’s going on,” he told Alzforum. Weintraub noted that patients do receive partial points for a mostly correct or related word.

Both Hodges and Meyer noted the sample size was small, but acknowledged how hard it is to recruit, test, and follow PPA patients to autopsy. Meyer said he is not using the 3W3S test with his PPA patients right now, but might in the future. A correct diagnosis during life helps patients and families know what to expect and someday may help determine the best drugs for therapy.

Weintraub plans next to explore relationships between structural MRI and the 3W3S test in patients with PPA to see which areas of atrophy correlate with impairments.—Gwyneth Dickey Zakaib

References

Paper Citations

- Weintraub S, Peavy GM, O'Connor M, Johnson NA, Acar D, Sweeney J, Janssen I. Three words three shapes: A clinical test of memory. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2000 Apr;22(2):267-78. PubMed.

Further Reading

Papers

- Botha H, Duffy JR, Whitwell JL, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Schwarz CG, Reid RI, Spychalla AJ, Senjem ML, Jones DT, Lowe V, Jack CR, Josephs KA. Classification and clinicoradiologic features of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) and apraxia of speech. Cortex. 2015 Aug;69:220-36. Epub 2015 May 27 PubMed.

- Bisenius S, Neumann J, Schroeter ML. Validating new diagnostic imaging criteria for primary progressive aphasia via anatomical likelihood estimation meta-analyses. Eur J Neurol. 2016 Apr;23(4):704-12. Epub 2016 Feb 22 PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Kielb S, Cook A, Wieneke C, Rademaker A, Bigio EH, Mesulam MM, Rogalski E, Weintraub S. Neuropathologic Associations of Learning and Memory in Primary Progressive Aphasia. JAMA Neurol. 2016 Jul 1;73(7):846-52. PubMed.

- Hodges JR. Pathological Diagnosis During Life in Patients With Primary Progressive Aphasia: Seeking the Holy Grail. JAMA Neurol. 2016 May 16; PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.