Exposure, Exposure, Exposure? At CTAD, Aducanumab Scientists Make a Case

Quick Links

There was a new feeling in the air at the 12th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference. It felt good: After decades of failure, the field might finally be turning a corner. The renewed optimism at the meeting, held December 4–7 in San Diego, was driven largely by Biogen’s shocking announcement last October that one of its two Phase 3 aducanumab trials, after a prior declaration of futility, was looking positive, after all. At CTAD, scientists got a look at some more of the data. It mostly opened a window on how protocol amendments midway through the trial slowly raised exposure among subsets of participants, and tried to link exposure to drug effect.

- Aducanumab exposure said to be tied to cognitive benefit in Phase 3.

- In a tiny tau PET sub-study, drug exposure correlated with fewer tangles.

- Anyone’s guess: Will FDA statisticians give thumbs-up on this dataset?

The audience wanted to see more data still. Even so, they found much to dissect in hallway conversations afterward, with many privately questioning whether the dataset is clean enough to garner marketing approval from the Food and Drug Administration. Nonetheless, the consensus was that the drug probably works. Why? It robustly removes amyloid, possibly clears tau tangles as well, and, at sustained high doses, may modestly slow decline. “All the data suggest this is a disease modification,” Paul Aisen of the University of Southern California, San Diego, noted in a panel discussion, though the panel was criticized as being too one-sided.

It wasn’t only aducanumab that fueled the hopeful mood. Presentations on gantenerumab, donanemab, and BAN2401 all described dramatic amyloid clearance that was sustained over time, although none discussed cognitive outcomes. Other talks also reported positive findings, with researchers getting their first look at detailed Phase 3 data of the anti-agitation drug pimavanserin in AD (Sep 2019 news). Ditto for AMBAR, whose sponsor, Grifols, had previously reported slowing of cognitive and functional decline in AD dementia (Nov 2018 conference news), and in San Diego added cerebrospinal fluid and FDG PET biomarker data, as well as additional statistical analyses.

“For the first time in my 25-year career, we had a conference with not one, but several positive readouts,” said Marwan Sabbagh of the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas. “We’re starting to make progress. This has reignited enthusiasm in the field.”

Cynthia Lemere of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who investigates anti-amyloid therapies, noted that Biogen’s previous announcement of futility had discouraged her (Mar 2019 news). “These new data have restored my faith in this approach,” she told Alzforum.

So what were the data? In October, Biogen had reported that 10 mg/kg aducanumab slowed cognitive decline by a quarter, and functional decline by 40 percent, in the EMERGE trial. By contrast, the biologic appeared to have no benefit in the identical ENGAGE trial, with placebo and treatment groups performing similarly, and the high-dose group, if anything, trending a tad worse on the primary outcome. The company ascribed the difference to mid-study protocol amendments that raised dosing and disproportionately benefitted EMERGE participants (Oct 2019 news).

In San Diego, Samantha Budd Haeberlein of Biogen elaborated on this point. The key amendment, protocol version 4 (PV4), allowed ApoE4 carriers to be titrated up to the 10 mg/kg dose. About two-thirds of study participants carried an E4 allele, and their dose had been previously capped at 6 mg/kg because of worries over ARIA. To examine the consequences of this dosing change, Budd Haeberlein divided the pooled EMERGE and ENGAGE cohort into people who had enrolled before PV4 was adopted in March 2017, and those who enrolled after. Eighteen percent of pre-PV4 participants received the full possible course of treatment—14 doses of 10 mg/kg—compared with 49 percent of post-PV4 participants. Overall, the amendment boosted the cumulative aducanumab exposure by a third, with the pre-PV4 group reaching a median cumulative dose of 116 mg/kg by the end of the study, and the post-PV4 group, 153 mg/kg. “Protocol 4 had a real impact on dosing,” Budd Haeberlein said.

ENGAGE had begun enrolling before EMERGE, hence fewer of its participants were affected by this protocol change. When PV4 was adopted, ENGAGE had 200 more participants than EMERGE. Each participant had to consent to the protocol change, and PV4 took 18 months to fully implement, Budd Haeberlein noted. As a result, by the end of the trial, 22 percent of ENGAGE patients had received the full course of 14 doses of 10 mg/kg, compared with 29 percent of EMERGE patients. To represent this, Budd Haeberlein showed exposure “heat maps” for ENGAGE and EMERGE of the dose each patient received at each visit. Dark blue indicated maximum dosage, and yellow no dose, providing a visual representation of dosing changes and interruptions. The EMERGE map showed a slightly thicker slice of solid blue than ENGAGE (see image below).

The Blues. More participants achieved 14 treatments at maximum dosage (dark blue) in EMERGE than ENGAGE, with fewer dosing interruptions (yellow). [Courtesy of Biogen.]

Budd Haeberlein showed a slide illustrating marked differences in how fast sites in the countries of these global trials consented their participants to PV4. Biogen issued PV4 in March 2017, and the majority of participants at U.S. sites were on it by December of that year, but participants in Italy and Poland only started signing on by then; in Portugal, signing started in spring of 2018. This implies differences by country, but Budd Haeberlein did not show exposure/efficacy data by country, and declined to answer questions about country or site effects.

Was Exposure the Key? A post hoc subgroup analysis of participants enrolled after maximum dosing was raised suggests a cognitive benefit in both trials (gray, placebo; purple, high dose). [Courtesy of Biogen.]

Biogen contends that participants need to reach this 14 x 10 mg/kg exposure to have a cognitive benefit. Budd Haeberlein showed a comparison of post-PV4 subgroups in ENGAGE and EMERGE, amounting to 886 participants in the former and 790 in the latter, roughly half of each cohort. In this post hoc subgroup analysis, 10 mg/kg aducanumab treatment appeared to slow CDR-SB decline by a similar amount in both trials, 27 percent in ENGAGE and 30 percent in EMERGE. Numerically, CDR-SB worsened by 1.76 points in EMERGE, with treatment reducing this by 0.53. CDR-SB worsened by 1.79 points in ENGAGE, with treatment cutting this by 0.48. In the whole ENGAGE cohort, the placebo group had declined more slowly, by 1.55 points.

Curiously, people who enrolled post-PV4 but were titrated to only 6 mg/kg fared nearly as well as the high-dose group, with a slowing of decline of 20 percent in ENGAGE and 24 percent in EMERGE. On graphs, both treatment groups tracked together (see image above).

The secondary outcome measures followed a similar pattern in this post hoc subgroup, Budd Haeberlein said, but she did not show those data, nor any further characteristics of those subgroups. She declined to address subsequent questions about these subgroups, except to say that their ApoE genotype distribution was as in the ITT population. Biogen believes the findings support the idea that sufficient exposure to drug slowed disease progression in both trials.

Conference attendees had a mixed reaction to this, with most wanting to see more detailed data. Dennis Selkoe at Brigham and Women’s Hospital said that the explanation makes sense to him, but he would like to see the secondary outcomes as well. “If they look similar, it would be compelling,” Selkoe told Alzforum. Henrik Zetterberg, University of Gothenberg, Sweden, essentially concurred, as did other leading researchers at CTAD. At the same time, they noted that other factors could have affected the results. Many wanted to see the percentage of ApoE4 carriers, as well as baseline values and demographic information of each subgroup, and suggested that imbalances there could have skewed the post hoc findings. Howard Feldman of the University of California, San Diego, Bruno Imbimbo of Chiesi Pharmaceuticals in Parma, Italy, and others suggested that a higher incidence of ARIA in treatment groups than controls could have effectively unblinded study participants and some study staff, leading to a placebo effect.

Lon Schneider of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said that researchers will need to see sensitivity analyses to know whether the drug effect is real (see full comment below). Others wanted to see spaghetti plots of the dose-response effect. In hallway talk, researchers grumbled that the presentation contained little new data beyond that released in October, and noted that Biogen is holding its cards close to the chest. Maria Teresa Ferretti of the University of Zurich spoke for many when she said, “I’m left with the same questions I had coming in.”

The biomarker data elicited more positive reactions. Budd Haeberlein reiterated amyloid PET findings, reporting consistent plaque removal that correlated with dose. At 6 mg/kg aducanumab, SUVR dropped by 0.17 in both studies. At 10 mg/kg, SUVR dropped by 0.24 in ENGAGE and 0.27 in EMERGE, with group sizes ranging from 74 to 203 people. As previously reported, CSF p-tau and t-tau dropped dose-dependently in EMERGE, though group sizes here were tiny, ranging from 14 to 29 people in a trial that enrolled 1,638 participants total. In ENGAGE, p-tau and t-tau reduction were not dose-dependent, with group sizes ranging from 16 to 21.

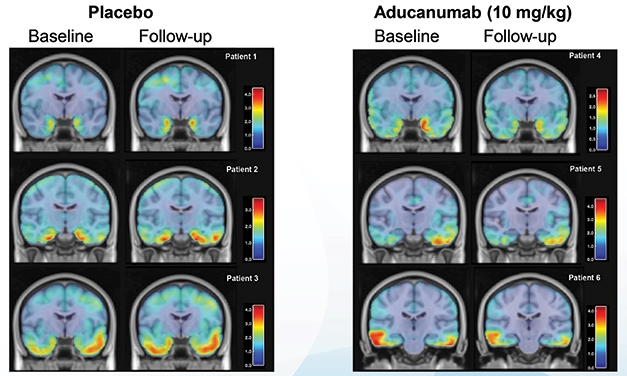

Tangle Cleanup? In a small tau PET sub-study, high-dose aducanumab lowered tracer uptake in medial temporal regions over 14 months. [Courtesy of Biogen.]

New in San Diego were tau PET data, using the second-generation tracer MK6240. Examining a medial temporal composite made up of hippocampus, parahippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and other anterior medial and lateral temporal lobe regions, the researchers found that the SUVR increased among people on placebo by about 0.09 over 14 months. For those on drug, the SUVR dropped by about 0.05 (see image above). The PET sub-study comprised 11 participants on placebo, 14 people on 6 mg/kg, and 11 on 10 mg/kg. The change in tracer uptake correlated inversely with dose. No correlation analyses were shown for amyloid removal versus CDR change.

“The tau PET data were impressive,” Eric Siemers of Siemers Integration LLC in Zion, Indiana, told Alzforum in San Diego. Siemers elaborated in writing (see below). Sabbagh, and others, speculated that a reduction of tau pathology might underlie the cognitive benefit.

In trials of aducanumab, as well as other anti-amyloid antibodies like BAN2401 and solanezumab, the cognitive benefit seems to lag behind amyloid removal, hinting it could be due to a downstream effect. Defining the lag time between amyloid removal and a cognitive benefit is a priority for future anti-amyloid trials, researchers agreed. Stephen Salloway of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, who was the lead site investigator for the aducanumab trials, noted that although the cognitive benefit seen in the aducanumab trials was small, the data overall suggest an effect on disease progression. “We’re looking for a biological foothold we can build on,” he said.

Across the board, researchers lamented the early termination of these trials, which led to an incomplete, confusing dataset. “The futility decision was highly unfortunate, and puts us in this position of having to analyze a complex dataset,” Aisen said. Budd Haeberlein agreed, but presented no data on the futility analysis. She noted that although Biogen will call patients back to resume dosing, they will have been off drug for varying numbers of months, further complicating long-term efficacy and biomarker data. The dosing changes midway through the trial clouded the picture, but Budd Haeberlein believes amending the protocol was the right decision under the circumstances. “I would not recommend changing the dose in the middle of a Phase 3 trial, but it turned out to be important for this study. Had we not done so, we would not have the results we do today,” she said in San Diego.

Audience members questioned whether the small cognitive benefit, amounting to a 23 percent slowing of decline on the CDR-SB, was meaningful. In the panel discussion, Sharon Cohen of the Toronto Memory Program, a site leader for the aducanumab trials, urged them to focus instead on the 40 percent slowing of decline in activities of daily living (ADL). “Eighty percent of the participants were in the prodromal stage, meaning they are living independently. The ability to continue to work, travel, bank, and enjoy leisure activities matters more to patients than what score they get on a memory test. In this disease, patients lose themselves slice by slice. Anything they can do to hang on is a triumph,” she explained. ADL was a secondary outcome measure. Some in the audience noted that such comments increase public pressure on the FDA to approve the drug, regardless of the unanswered scientific questions, and efficacy data resting largely on one incomplete Phase 3 trial.

Will these data be enough for regulators to allow Biogen to market aducanumab? Many were skeptical. Feldman noted that the FDA might find the risk-benefit ratio insufficient. Although ARIA was manageable and the field in general is less acutely concerned about this phenomenon now than when ARIA first cropped up, its incidence was high. Altogether, 25.8 percent of participants on 6 mg/kg, and 35.1 percent of those on 10 mg/kg, developed ARIA-E, a form of brain swelling. This compared with 2.3 percent of the placebo group. Most ARIA occurred in ApoE4 carriers. For a large majority it was asymptomatic, but about a quarter of those with ARIA complained of headaches, dizziness, or nausea.

In addition, some participants developed ARIA-H, indicating microhemorrhages. These occurred in 17.5 percent of people on drug, versus 6.8 percent of controls. This incidence is higher than in other antibody trials; for example, the Marguerite RoAD extension study of high-dose gantenerumab reported 9 percent (Aug 2018 conference news). ARIA-H has received less attention in AD trials than ARIA-E, with clinicians saying this phenomenon worries them less. Like ARIA-E, it is usually asymptomatic. Seven people on aducanumab and four controls had more extensive brain bleeds. Overall, 31.7 percent of people on 6 mg/kg and 40.7 percent of those on 10 mg/kg experienced some form of ARIA, compared to 10 percent of controls.

Whether aducanumab will be approved is a huge question the FDA and international regulators will decide. That aside, though, most researchers at CTAD saw a deeper significance for the field in these new data. “Everyone I’ve talked to agrees that this validates amyloid as a target,” Selkoe said. Aisen went further. “The lesson here is that the amyloid hypothesis is going to yield effective therapies,” he predicted. Slides of Budd Haeberlein’s presentation are available on Biogen’s website.—Madolyn Bowman Rogers

References

Therapeutics Citations

News Citations

- Phase 3 Trial Suggests Pimavanserin Assuages Psychosis in Dementia

- Fits and Starts: Trial Results from the CTAD Conference

- Biogen/Eisai Halt Phase 3 Aducanumab Trials

- ‘Reports of My Death Are Greatly Exaggerated.’ Signed, Aducanumab

- Four Immunotherapies Now Banish Amyloid From the Brain

Other Citations

External Citations

Further Reading

News

- Keep Your Enthusiasm? Scientists Process Brutal Trial Data

- Much ‘Adu’ About a Little: Phase 1 Data Feeds the Buzz at CTAD

- Paper Alert: Aducanumab Phase 1b Study Published

- Gantenerumab, Aducanumab: Bobbing Up and Down While Navigating Currents of Trial Design

- Aducanumab, Solanezumab, Gantenerumab Data Lift Crenezumab, As Well

- Biogen Antibody Buoyed by Phase 1 Data and Hungry Investors

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine

Protocol amendments during the trials increased the dose for APOE4 carriers from 6 to 10 mg/kg, allowed restarting aducanumab in people with ARIA who more likely than not were APOE4 carriers, and increased the size of each trial to 1,605. It’s important that Biogen designed the trials with a planned futility analysis when about 50 percent of the anticipated 1,605 in each trial had had the opportunity to complete 18 months. These numbers were 803 and 945 in EMERGE and ENGAGE, respectively. Biogen must have determined that the amendments would not affect the validity of the trials, the precision and effect sizes of the outcomes, the drug-placebo differences, and that the futility analysis would serve its purpose.

Biogen likely would have walked away from aducanumab had it not examined outcomes again after adding the 179 and 139 participants, respectively, who continued during the time it took to do the futility analysis. The additional participants appeared to bring the nonsignificant CDR-SB efficacy analyses in the futility samples to nominal significance of P=0.01 for EMERGE, but not for ENGAGE, P=0.83, with a CDR-SB difference of -0.38 points favoring aducanumab in the former, and +0.05 in the latter. There are good reasons for Biogen to now think that the futility methods were ill-considered. As trials are designed for perfection, interim analyses are inherently misleading. They are undersized; effects can vary randomly in relation to the true effect (that now can’t be determined); and significant effect sizes tend to be biased upward. Both the futility analysis and subsequent analysis are interim analyses.

With two curtailed trials, Biogen is now in the world of post hoc, exploratory analyses on small, often incomparable subsets, and where about 50 percent of the samples did not complete the 78 weeks, most administratively terminated early. This is made more complicated and uncertain because the original trials sought to detect a very small 0.5-point CDR-SB difference as clinically important, which is a level at the limits of reliable detection, at least according to Roche statisticians presenting in San Diego. In this uncertain world of multiple comparisons and subsets, effect sizes and P values (which shouldn’t be used at this point) can change dramatically.

Biogen is offering selected, arbitrary, and incomplete post hoc analyses to make a claim that aducanumab is indeed effective (and it might very well be). These analyses are inadequate, however, because they don’t distinguish the samples, don’t show the important baselines and demographics, or the effects of the covariates, and don’t show both subsets when they split the samples. There are probably subsets that don’t show advantages for aducanumab; those subsets haven’t been revealed.

What Biogen needs to show first are the actual methods for the futility analyses, calculations of the conditional probabilities, the efficacy analyses associated with the futility sample, and then the efficacy analyses associated with the final available samples of 982 and 1,084. Without the methods and results for the futility analysis, we don’t know how or why the DSMB or other body recommended to stop the trials. Only once Biogen contrasts these two analyses will we be able to understand how the added participants influenced the outcomes of both trials. Sensitivity analyses are then needed to assess the potential for bias due to dropouts, AEs, ARIA, unblinding due to MRI/ARIA, APOE4 carriage, and the effects of the covariates in the statistical model (e.g., baseline severity, APOE4 status, sites, etc.). Most likely Biogen has done this; it hasn’t disclosed it.

Simply noting that an earlier and later subset of APOE4 participants received different cumulative dosing does not demonstrate that dosing determined clinical outcomes. In their subset analysis at the end of their presentation, they demonstrate CDR-SB outcomes of the 879 and 790 participants in EMERGE and ENGAGE, respectively, who were randomized after amendment 4 was implemented, which allowed 10 mg/kg for APOE4 carriers. They show that, in this latter half of the study, the outcomes in the high-dose groups were the same in both trials at -0.53 and -0.48 CDR-SB points with 95 percent CIs that included 0 in 3 of 4 dose comparisons.

But Biogen don’t show the first half of the study samples, i.e., the complementary subset that they created. These outcomes, however, can be determined algebraically, as sample sizes of approximately 751 and 857; placebo-group declines over 78 weeks as 1.72 and 1.35; the low dose placebo-aducanumab differences as -0.04 and -0.02; and high dose differences as -0.25 and +0.43.

Most remarkable is the placebo change in one ENGAGE subset and then the marked worsening of the high dose of +0.43. It is hard to explain how one placebo group of about 298 participants differed from three identically selected, similarly sized groups except by randomness. Here again, more sensitive analysis is needed to hope to gain an explanation. Similarly, it is hard to explain how high-dose aducanumab caused a +0.43-point CDR-SB difference favoring placebo in one subset and opposite directional effects of -0.25 to -0.53 in the other dose groupings. Biogen gives us, in its apparently best-case scenario, an example of how variable these CDR-SB effects may be, and why careful post hoc analyses, sensitivity analysis, and appreciation of uncertainty is needed.

Biogen would not be presenting at all unless it completed all post hoc analyses it thought had to be done. It is problematic that it told Wall Street analysts that this was not the time to present subgroups. It appears we won’t gain a fuller appreciation of Biogen’s data, analyses, and inferences until and unless there is an FDA advisory committee meeting, when FDA will post their detailed statistical and clinical reports. Until then, there is little information to support Biogen’s efficacy and safety claims, and for stakeholders to evaluate.

Siemers Integration LLC

Samantha Budd Haeberlein’s presentation of top-line results regarding the Phase 3 trials of aducanumab was based largely on analyses that included more data than those used to determine that the studies were futile in March 2019. Most of the presentation was based on data obtained until the press release that communicated the result of the futility analysis. Importantly, all data after the press release were censored to avoid bias in those determinations.

The data set used to determine futility included information from 803 participants in EMERGE and 945 participants in ENGAGE. The intent-to-treat (ITT) data set that included additional data until the March press release included information from 1,638 participants in EMERGE and 1,647 participants in ENGAGE. A subset of the ITT population was those participants who had the opportunity to reach endpoint; the numbers of participants for those analyses were 982 and 1,084 for EMERGE and ENGAGE, respectively. The “opportunity to reach endpoint” subgroup was smaller than the entire ITT population, but was more analogous to the data used to make the futility analysis. Further complicating the analyses, a major protocol amendment was made during the studies that allowed participants who were apolipoprotein E4 carriers to increase their dose to 10 mg/kg.

Using the ITT population, the EMERGE study did meet the original primary outcome, the CDR-SB, in the “high-dose” group. The ENGAGE study, however, not only did not meet statistical significance, but in the ITT population there was not even a trend in the CDR-SB in the high-dose group. For the secondary outcome measures, MMSE, ADAS-cog13 and ADCS-ADL-MCI, for the EMERGE study the drug effect was generally of the same magnitude as the effect on the CDR-SB. For the ENGAGE study, trends favoring drug were present for the ADAS-cog13 and ADCS-ADL-MCI, but not for the MMSE. Interestingly, CSF p-tau showed a dose-dependent decline in the EMERGE study, but not in the ENGAGE study. Although based only on a small number of participants, tau PET showed a dose-dependent effect when pooling both studies.

Given that Biogen has publicly stated that it plans an FDA submission, the likelihood of regulatory approval has been given a great deal of attention. The FDA and other regulatory agencies will be given a difficult decision, especially given the overwhelming unmet need. Should regulatory agencies approve aducanumab (with post-marketing commitments) based on a package that does not meet usual criteria and cannot be considered unequivocal, or should they require an additional placebo-controlled trial that will require at least three years? That decision will be difficult and will likely be influenced by an advisory committee discussion.

Perhaps most important for the scientific field of AD research is the fact that based on the totality of the data, even with the complications regarding the dose change, aducanumab appears to be having some effect on disease progression. Additional PK/PD analyses will be helpful in this regard.

These results should be placed in context of the Phase 2 BAN2401 results, which, despite the limitations of Phase 2 studies, were consistent with an effect of the drug on disease progression. Additionally, the solanezumab results taken from the three EXPEDITION studies suggest that an effect of the drug, albeit small, was present. Each of these antibodies binds to different species of Aβ and amyloid, with different affinities. With additional research, identification of the most toxic species and more precise targeting could result in an increase in efficacy while reducing adverse effects such as ARIA.

Taken together, the findings related to aducanumab, BAN2401, and solanezumab represent an important toehold in the fight against AD.

University of Gothenburg

I felt quite positive after having listened to the presentation. I understand better what happened in the futility analysis. I would like to see plasma p-tau concentrations in all subjects. I would also like to learn more about plasma neurofilament light concentrations in relation ARIA, as well as amyloid removal.

Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A.

I offer a discussion point on the treatment effects of the aducanumab high dose in the EMERGE study. They were:

+0.50 points on MMSE (cognition)

-1.4 points on ADAS-Cog (cognition)

-0.40 points on CDR-SB (clinical status)

+1.7 points on ADCS-ADL-MCI (functionality)

Could the treatment effect have been influenced by the unblinding caused by the occurrence of ARIAs (34.4 percent on high dose vs 2.2 percent on placebo)? Unblinding may affect the performance of the patient and the judgement of the caregiver and the rater.

The treatment benefit on MMSE was minimal (0.5 points versus a mean placebo decline of 3.3 points). Interestingly, the MMSE scale is based only on objective patient performance; it does not include subjective input by the rater or caregiver. The treatment effect of aducanumab on MMSE did not reach statistical significance in spite of large sample size per treatment arm (n = 545).

The treatment benefit on ADAS-Cog was modest (1.40 points versus a mean placebo decline of 5.17 points). The ADAS-Cog contains three “subjective” items that are scored by the rater (comprehension of spoken language, word-finding difficulty, spoken language ability).

The treatment benefit on the CDR-SB appears more robust (0.40 points versus a mean placebo decline of 1.74 points). This scale assesses six domains of cognitive and functional performance obtained through a semi-structured interview of the patient and the caregiver.

The treatment effect on ADCS-ADL-MCI appears significant (1.7 points versus a mean placebo decline of 4.3 points). This scale is entirely based on a structured interview with the caregiver.

Thus, it appears that in the EMERGE study, aducanumab’s benefit on the different scales is proportional to the extent of the subjective input of the caregiver and the rater. A similar phenomenon is visible in the ENGAGE study.

Could it be that the degree of unblinding in EMERGE was greater than in ENGAGE because more patients were exposed to the highest dose? Since ARIAs occurred more frequently in APOE4 carriers than in noncarriers (42.5 percent versus 17.9 percent) treated with the high dose, it would be interesting to verify if the treatment effect of the high dose of aducanumab was larger in the APOE4 carriers than noncarriers, possibly due to higher unblinding?

Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine

As a behavioral neuroscientist and toxicologist, when I look at the data and see the visually overt correlations between the overall time-dependent slopes of those lines, and the lack of consistent improvement across all measures of behavioral function, especially when these data are considered in terms of the increased risk for ARIA-E in the high-dose group, it is hard for me to see how the FDA will grant approval for this drug without additional studies.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.