Amyloid Scans in the Clinic: Seeing Is Believing?

Quick Links

Amyloid scans have allowed researchers to follow Alzheimer’s pathology as it develops in the human brain, but they are still working out whether and how this technology will help patients. At the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2015, held July 18 to 23 in Washington, D.C., scientists presented results of three recent trials that examined whether scans led to changes in patient diagnoses, influenced how doctors managed their disease, or improved health outcomes. These studies aim to help doctors and insurers define which patient groups will benefit the most. “We want to be very cautious in how we use these expensive instruments and tease out the populations that really need imaging,” said Philip Scheltens, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam.

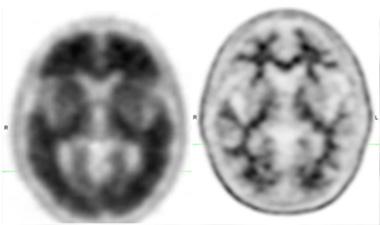

The largest of the studies comes from Philadelphia-based Avid Pharmaceuticals, owned by Eli Lilly and Company in Indianapolis. Avid makes the amyloid ligand florbetapir, aka Amyvid. Company scientists completed a randomized Phase 4 study of positron emission tomography (PET) scans with the tracer to test short-term consequences on diagnosis and patient management, as well as longer-term health outcomes. Avid’s Michael Pontecorvo presented results at AAIC. The trial enrolled 618 patients aged 50 to 91, with an average age of 73, from France, Italy, and the United States. All had a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or dementia, but physicians were less than 85 percent certain that AD pathology underlay their symptoms. Doctors first gave a working diagnosis and outlined would-be plans for treatment and further testing in the absence of a scan. Then, all patients were scanned for brain amyloid (see image below).

Scans in the Clinic.

Amyvid PET scans distinguished between brains with high (left) and low (right) amyloid. [Courtesy of Eli Lilly & Co. and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals.]

For 308 of them, participating physicians received results right away and some used them to modify their action plan. The researchers compared outcomes in that patient group with outcomes from 310 patients who served as a control group—this "delayed feedback" group got their scan results a year later. The researchers wanted to know if outcomes would change with or without knowledge of amyloid status.

Three months after scanning, the participating physicians recorded for the researchers any modifications they had made to their original diagnoses and any further tests or treatments they had ordered or prescribed. Doctors who got scan results immediately changed their diagnosis for a third of patients, most often to fit a scan that countered their original thinking. For patients who initially had a non-AD diagnosis but a positive scan, scan results changed the doctor’s mind 92 percent of the time. Conversely, doctors switched to a non-AD diagnosis in 81.5 percent of cases considered AD at the outset when the scan was negative. In the delayed-feedback control group, physicians altered only about 6 percent of diagnoses, for reasons other than amyloid PET scan results.

Doctors altered their treatment strategy in 68 percent of patients in the experimental group, versus 56 percent in the control group, a statistically significant difference. These numbers were driven mostly by prescription of cholinesterase inhibitors: In the group that got scan results immediately, physicians began prescribing these drugs to people with positive scans and discontinued them in those with negative scans. In the delayed-feedback group, doctors prescribed more of these drugs to everyone.

Patients returned for one-year follow-up appointments so doctors could assess change in cognitive status, health outcomes, mood, function, or quality of life. There was no difference between groups. The study lacked the power to discern small or rare effects, Pontecorvo said. He added that the company found no evidence that disclosing amyloid status to patients or their caregivers led to higher rates of depression, anxiety, or drug use (see Aug 2015 conference news).

“The study shows how amyloid imaging is likely to change clinical practice,” said Glenda Halliday, Neuroscience Research Australia, Randwick, New South Wales, who co-chaired the session with Matthew Frosch, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. Frosch cautioned against weaknesses in the data. For instance, Pontecorvo did not collect data on what the alternative diagnoses had been, or reasons for maintaining disease management that ran counter to scan results.

“This study demonstrates that in diagnostically uncertain cases, amyloid PET can help refine diagnosis and guide clinical management,” said Gil Rabinovici, University of California, San Francisco. It also suggests that amyloid PET disclosure is safe in a clinical setting, he said. Rabinovici leads the IDEAS study, a separate effort to examine benefits of amyloid scans in Americans 65 years and older (Apr 2015 news). He was surprised by the high rate of management change in the control group. It could be explained by clinicians not knowing whether scan feedback would be immediate or delayed when they completed the pre-PET management plan, he said, so they may have held off on final management recommendations hoping they could incorporate amyloid status into their decision. “In IDEAS, we will compare disease management that assumes amyloid PET will not be accessible with management that occurs after an amyloid scan,” he told Alzforum. “This design may better isolate the impact of the scan.”

A different study, from Scheltens’ lab, tested the utility of amyloid scans in patients with an earlier age at onset of disease. Marissa Zwan pointed out that scans give valuable information in younger people, because they are less likely to have age-related amyloid deposits in their brain, have fewer comorbidities, and more likely to have a form of dementia that is harder to diagnose because of overlapping clinical phenotypes, for example frontotemporal dementias.

Patients were eligible to take part if their neurologist said they were less than 90 percent certain of the cause of their dementia after a standard clinical workup. This included a neurological and psychiatric screen, as well as a magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain. The study included 211 patients with an unclear, atypical presentation of dementia, who ranged from 45 to 70 years old. Of those, 145 were tentatively diagnosed with AD, 66 with a non-AD dementia. All got a flutemetamol PET scan, and the results were given to the clinician, who then re-evaluated the diagnosis and revised their measure of confidence and management plan.

Eighteen percent of patients originally thought to have AD had negative brain amyloid scans. This led their clinician to diagnose another disease, such as frontotemporal dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Twenty-three percent of those with a non-AD diagnosis had a positive scan. This led the clinician to pronounce AD as the underlying cause, though in one case they pinpointed DLB. Doctor confidence increased for 86 percent of patients. The doctors changed how they managed disease for 37 percent of the patients, again driven mostly by medication changes. Patients initially labeled AD whose scans were negative went on for more diagnostic tests, probably to seek evidence for an alternative cause of the dementia, said Zwan.

“This confirms that amyloid PET imaging does have an impact on clinical diagnosis and patient management,” said co-author Femke Bouwman. Zwan agreed, adding, “It’s really important to determine in which patients the use of this technology will add value.” She pointed out that while appropriate-use criteria have been proposed (Johnson et al., 2013), they still need to be validated by evidence from the field, especially in a memory clinic setting.

Scheltens noted that the IDEAS study enrolls only people 65 and older—the minimum age for Medicare coverage—and so will miss out on testing a younger population that could gain more from a scan. Rabinovici agreed that examining younger patients is important, saying he and colleagues are brainstorming about a parallel study to do that.

Robert Laforce, Hôpital de l'Enfant-Jésus, Quebec, presented similar results from a small study of 25 subjects. He used F18-labelled NAV4694 (see Oct 2014 news) to test how amyloid PET affects diagnosis and clinician confidence. Laforce also assessed the impact on caregivers. Participating patients were younger than 65, with an average age of 59. For nine of them, physicians changed their diagnosis after the scan: six to a non-AD diagnosis and three to AD. Overall diagnostic confidence rose from 63 percent to 88 percent. Post-scan treatment plans changed in 18 patients, including changes in medication or referral to other research projects. Treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors began in everyone with a positive scan who had taken none before, whereas most recipients with a negative scan stopped taking them.

Assessing caregiver impact proved less straightforward. Caregivers reported less anxiety and depression, but didn’t feel strongly one way or the other about the value of the scan. Laforce interprets this to mean that people appreciate a more certain diagnosis but are generally unhappy that their loved one has developed a degenerative disease. One audience member noted that the scientists did not assess caregiver status prior to the scan. Bouwman explained the researchers could have missed an important change as a result. She said that future studies by other groups should likewise add a focus on caregivers.

While the percentage benefit varies some, these studies suggest that the most eligible patient groups for a scan are those for whom doctors are uncertain of an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, and that in this group, diagnosis and treatment may change. Whether insurers will decide to cover amyloid PET is unclear. For that decision, in the United States at least, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will look to the IDEAS study to see if scans lead to better outcomes. IDEAS will enroll 18,500 participants and is powered to detect whether short-term changes in management translate to better long-term outcomes.—Gwyneth Dickey Zakaib

References

News Citations

- How Do You Communicate Alzheimer’s Risk in the Age of Prevention?

- $100M IDEAS: CMS Blesses Study to Evaluate Amyloid Scans in Clinical Practice

- Lilly Teams Up With AstraZeneca for BACE Inhibitor Phase 2/3 Trial

Paper Citations

- Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, Donohoe KJ, Foster NL, Herscovitch P, Karlawish JH, Rowe CC, Carrillo MC, Hartley DM, Hedrick S, Pappas V, Thies WH. Appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET: a report of the Amyloid Imaging Task Force, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the Alzheimer's Association. J Nucl Med. 2013 Mar;54(3):476-90. PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Ossenkoppele R, Prins ND, Pijnenburg YA, Lemstra AW, van der Flier WM, Adriaanse SF, Windhorst AD, Handels RL, Wolfs CA, Aalten P, Verhey FR, Verbeek MM, van Buchem MA, Hoekstra OS, Lammertsma AA, Scheltens P, van Berckel BN. Impact of molecular imaging on the diagnostic process in a memory clinic. Alzheimers Dement. 2012 Nov 16; PubMed.

- Chiotis K, Carter SF, Farid K, Savitcheva I, Nordberg A, Diagnostic Molecular Imaging (DiMI) network and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Amyloid PET in European and North American cohorts; and exploring age as a limit to clinical use of amyloid imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015 Sep;42(10):1492-506. Epub 2015 Jul 2 PubMed.

- Sánchez-Juan P, Ghosh PM, Hagen J, Gesierich B, Henry M, Grinberg LT, O'Neil JP, Janabi M, Huang EJ, Trojanowski JQ, Vinters HV, Gorno-Tempini M, Seeley WW, Boxer AL, Rosen HJ, Kramer JH, Miller BL, Jagust WJ, Rabinovici GD. Practical utility of amyloid and FDG-PET in an academic dementia center. Neurology. 2014 Jan 21;82(3):230-8. Epub 2013 Dec 18 PubMed.

- Grundman M, Pontecorvo MJ, Salloway SP, Doraiswamy PM, Fleisher AS, Sadowsky CH, Nair AK, Siderowf A, Lu M, Arora AK, Agbulos A, Flitter ML, Krautkramer MJ, Sarsour K, Skovronsky DM, Mintun MA, . Potential impact of amyloid imaging on diagnosis and intended management in patients with progressive cognitive decline. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013 Jan;27(1):4-15. PubMed.

- Zannas AS, Doraiswamy PM, Shpanskaya KS, Murphy KR, Petrella JR, Burke JR, Wong TZ. Impact of ¹⁸F-florbetapir PET imaging of β-amyloid neuritic plaque density on clinical decision-making. Neurocase. 2014 Aug;20(4):466-73. Epub 2013 May 14 PubMed.

- Mitsis EM, Bender HA, Kostakoglu L, Machac J, Martin J, Woehr JL, Sewell MC, Aloysi A, Goldstein MA, Li C, Sano M, Gandy S. A consecutive case series experience with [18 F] florbetapir PET imaging in an urban dementia center: impact on quality of life, decision making, and disposition. Mol Neurodegener. 2014 Feb 3;9:10. PubMed.

- Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, Donohoe KJ, Foster NL, Herscovitch P, Karlawish JH, Rowe CC, Hedrick S, Pappas V, Carrillo MC, Hartley DM. Update on appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET imaging: dementia experts, mild cognitive impairment, and education. J Nucl Med. 2013 Jul;54(7):1011-3. PubMed.

News

- Alzheimer’s Community Mobilizes to Show Benefits of Amyloid Scans

- Coverage Denial For Amyloid Scans Riles Alzheimer’s Community

- Approved Amyloid Imaging Agents Work About Equally Well

- Three’s Company: Florbetaben Approved, Excludes AD Diagnosis

- Amyvid Follows in PiB’s Footsteps

- FDA Approves a Second Amyloid Imaging Agent

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.