Trial-Ready Cohorts Take Shape in Europe and U.S.

Quick Links

To speed up recruitment into Alzheimer’s trials, researchers have created innovative new platforms that establish trial-ready cohorts of people at early disease stages. The farthest along is the European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia Trial-Ready Cohort (EPAD-TRC), followed by the Trial-Ready Cohort for Preclinical/Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease (TRC-PAD) in the U.S. Both launched in 2014. At the 11th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference, held October 24–27 in Barcelona, Spain, leaders of both initiatives gave updates. EPAD is about to release baseline data from its first 500 participants, and will begin its first therapeutic trial in a year, while TRC-PAD is filling up its online registry and will begin in-person screening next year. Researchers hope that TRCs will be game-changers for trial enrollment. “The goal is to have no screen failures in trials,” Ritchie said.

- EPAD researchers release baseline data on first 500 participants.

- First EPAD trial to begin in 2019.

- TRC-PAD will start in-person screening for its trial-ready cohort next year.

Both initiatives take similar approaches, recruiting from existing registries and trials and screening those participants for amyloid positivity. Those who pass become part of a deeply phenotyped longitudinal cohort that provides a pool of participants to be tapped on an ongoing basis for therapy trials (Aug 2016 conference news; Aug 2016 conference news).

In Barcelona, Lisa Vermunt of VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, and Pieter Jelle Visser of Maastricht University in the Netherlands showed an analysis of how efficiently EPAD had recruited. They examined a subset of participants drawn from four feeder cohorts: the population-based Generation Scotland, the ALFA study in Barcelona, the Dutch Brain Health Registry, and the French Trial Registry. Together, these cohorts comprised 16,877 non-demented participants. Using a prescreening algorithm that took their age, APOE status, memories, and family histories into account, researchers invited 3,009 of those 16,877 people for clinic visits. Alas, only 414 people took them up on the offer and met all inclusion/exclusion criteria. Of those, 332 so far have undergone lumber punctures. 110 people were under the cutoff for amyloid positivity, with CSF Aβ42 below 1,098 pg/ml.

What predicted successful enrollment? The researchers found that older or less-educated people were less likely to show up for a scheduled in-person screening. Since both those factors increase the risk of AD, this results in losing many high-risk people from the cohort, Visser suggested. In addition, women were less likely than men to come in, again depleting a potentially higher-risk group. On the other hand, people with family histories of dementia were more likely to follow through with screening.

The large Generation Scotland cohort, 13,681 strong, had the lowest response rate to the study invitation, perhaps because researchers notified them by regular mail, Visser said. On the other hand, people recruited from memory clinics and smaller registries were more likely to come in and to stick with the process. Almost half of those from the French Trial Registry, which recruits from memory clinics throughout France, ended up undergoing CSF testing, while only about one in 200 of those from Generation Scotland did. Selecting from higher-risk populations boosts the screen success rate, Visser noted.

Among those who donated CSF, people who were older or carried an APOE4 allele were more likely to be amyloid-positive, as expected. Adding a plasma Aβ test before drawing CSF could reduce screen failures at this last step, Visser suggested (see Part 3 of this series).

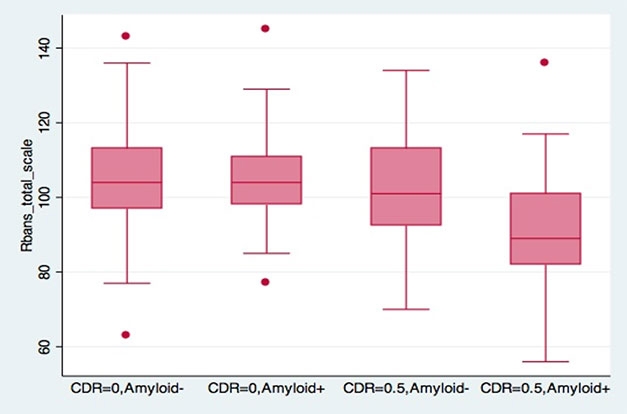

Early Decline in EPAD. The RBANS cognitive composite picks up subtle deficits in people at CDR 0.5; these are most pronounced in those with amyloid plaques. [Courtesy of Craig Ritchie.]

So where does the EPAD trial-ready cohort stand now? Craig Ritchie of the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, who co-leads EPAD, told researchers in Barcelona that as of October 2018, 1,111 people had been enrolled. Initially EPAD aimed for a cohort size of 6,000 but it has since dropped this target, trying now to recruit only as many people as are needed for trials. After a slow start in 2016, enrollment accelerated, and sites are now adding 100 participants per month. Since mid-2017, study investigators have been prioritizing recruiting from clinics over population cohorts, Ritchie said. He added that almost all participants have stayed in the study so far.

Because recruitment will continue throughout EPAD’s lifetime, investigators periodically lock data sets to facilitate comparisons of research findings from this cohort over time. They have just locked the first set, comprising baseline data from the first 500 participants. Ritchie noted that EPAD collects a vast amount of data, following good clinical practice (GCP) standards to support its use later on as people enter therapy trials. Participants are followed over time, providing run-in data for these trials.

The first 500 participants have a mean age of 66, and 52 percent are female. A majority, 59 percent, have a family history of dementia, but only 37 percent carry an APOE4 allele. Ritchie noted this is close to the population average of around 25 percent APOE4 carriers, and well below the proportion seen in most clinical and trial cohorts. “This is almost a community-based cohort,” he explained. A large majority are cognitively healthy, with a cohort mean MMSE of 28.6; 83 percent of them have a CDR of zero, though 17 percent are mildly impaired with a CDR of 0.5.

On biomarker analysis, 35 percent met the CSF Aβ42 cutoff for positivity. EPAD does not disclose amyloid status to participants. Amyloid-positive participants were more likely to be older, carry an APOE4 allele, and have a CDR of 0.5. Other characteristics, including sex, education, and family history, did not affect amyloid status. Based on these data, researchers developed an algorithm for predicting amyloid positivity using age, genotype, and CDR. The algorithm achieved a positive predictive value of 80 percent, and negative predictive value of 65 percent. Ritchie hopes its use may boost the success rate of screening as EPAD continues to enroll.

Comparing several different cognitive tests, researchers found the RBANS to be the most sensitive measure of decline. It related closely to the CDR, with people at 0.5 testing slightly lower on several RBANS subtests, particularly those related to memory. People who were CDR 0.5 and amyloid-positive had a more marked drop.

Michael Ropacki of Strategic Global Research & Development, Half Moon Bay, California, elaborated on this in a poster. At baseline, amyloid-positive and –negative participants differed on the RBANS, but did not vary much on the MMSE or on neuropsychological tests, he reported. Moreover, 37 percent of the cohort hit the ceiling on the MMSE, while 71 percent scored at floor on the Amsterdam Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire, indicating no functional impairment. Ritchie said the RBANS will be the primary outcome measure in the EPAD trial (Ritchie et al., 2017). “It is looking good as a tool to measure change over time,” Ritchie said.

This first EPAD dataset, V500.0, will be released to members of the EPAD consortium in December. Consortium members have six months of privileged access, and in summer 2019 the data will become publicly available worldwide. Ritchie expects to release the first year of follow-up data on these 500 participants, data lock V500.1, to the consortium in summer 2019; if recruitment stays on pace, baseline data on the first 1,500 participants (V1500.0) will come out at that time, too. The first proof-of-concept trial is expected to start in 2019 or 2020, and will include three interventions in different arms.

The TRC-PAD cohort is not as far along. This initiative is funded by the National Institute on Aging, and led by Paul Aisen of the University of Southern California, San Diego, Reisa Sperling of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Jeffrey Cummings of the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas. Initially, the Global Alzheimer’s Platform (GAP) planned to support the project as well, but was not able to provide any funding, Aisen noted.

In Barcelona, Gustavo Jimenez Maggiora of USC noted that TRC-PAD draws on existing U.S. registries such as the Brain Health Registry, the Alzheimer’s Prevention Registry, the Cleveland Clinic’s Healthy Brains.org, and the Alzheimer Association’s TrialMatch, as well as from trials such as the enormous Imaging Dementia–Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) cohort. People in these studies are invited to join the TRC-PAD registry, aka Alzheimer Prevention Trials (APT) Webstudy.

The APT Webstudy is an internet-based platform that launched in December 2017. Upon joining, participants fill out forms on their demographic data, family and medical history, lifestyle, and medications. They take Cogstate card tests and the Cognitive Function Index (CFI) at baseline and every three months thereafter. Tests take less than 20 minutes to complete. In addition, participants are referred for APOE genotyping.

Currently, 7,400 people are in the APT Webstudy, out of a planned 50,000. Seventy percent are women, and 93 percent are white. They tend to be highly educated, with 85 percent having at least some college. Their mean age is 64. They come from every state, but participants cluster in the southwest U.S., the mid-Atlantic states, and Florida. About 40 percent of them access the website via mobile devices.

To select people for the trial-ready cohort, the researchers will use an algorithm that takes test scores and APOE genotype into account, as well as prior biomarker or clinical findings available from participants. The selected participants will be invited to come to a clinic for in-person screening, and if eligible, will be enrolled in TRC-PAD. This in-person screening will begin in 2019, Jimenez-Maggiora said. Screening will start at eight sites and ramp up to 30 sites across the U.S., Aisen told Alzforum. Researchers will screen for plasma Aβ and follow up with CSF or PET to confirm amyloid status. Participants will take the PACC cognitive composite. Those enrolled into TRC-PAD will continue to take quarterly online cognitive tests, and return to the clinic for semi-annual visits. In this way, there will be run-in data for each participant before he or she enrolls in trials. Jimenez-Maggiora noted that TRC-PAD will expand to other countries as well. Japan’s effort will be led by Takeshi Iwatsubo at the University of Tokyo, and France’s by Bruno Vellas of Gerontopole in Toulouse.—Madolyn Bowman Rogers

References

News Citations

- Coming to a Center Near You: GAP and EPAD to Revamp Alzheimer’s Trials

- Access: How to Bring People in ‘From the Wild’?

- Blood Tests for Amyloid Step Out at CTAD

Paper Citations

- Ritchie K, Ropacki M, Albala B, Harrison J, Kaye J, Kramer J, Randolph C, Ritchie CW. Recommended cognitive outcomes in preclinical Alzheimer's disease: Consensus statement from the European Prevention of Alzheimer's Dementia project. Alzheimers Dement. 2017 Feb;13(2):186-195. Epub 2016 Oct 1 PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.