Small Brain Bleeds Lead To Bigger Problems in Alzheimer’s

Quick Links

Tiny brain bleeds in Alzheimer’s patients put them at a higher risk of stroke and cardiovascular disease. Which one develops depends on where those microbleeds occur, according to the latest findings from the MISTRAL Study. Scientists led by Wiesje van der Flier, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, report that AD microbleeds in deep non-lobar regions of the brain, such as the basal ganglia, associate with cardiovascular problems and related mortality. In contrast, those in the outer lobar regions of the brain foretell stroke and stroke-related death. The findings, reported in the March 23 JAMA Neurology, could have implications for understanding subtypes of the disease and conducting Aβ immunotherapy trials.

Tiny Hemorrhages Make Their Mark:

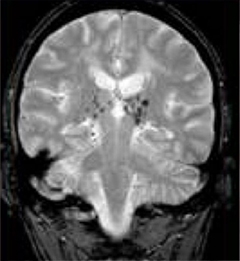

Microbleeds (small black spots), visible by MRI, are left behind after small blood vessels rupture. [Image courtesy of Dr Robert Carlier and Dr Frédéric Colas, CHU Raymond Poincaré, Garches, France.]

“The findings are really very striking,” said Costantino Iadecola, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. “[The study] separates two different groups of patients based on the location of these microscopic abnormalities. This is the first time such a regional specification has been so clear-cut.”

Microbleeds, especially in the lobar region, are more common in AD than in the general population (Cordonnier et al., 2006). Van der Flier and colleagues previously reported that these ruptures of teeny blood vessels predicted mortality in AD (Hennemen et al., 2009). However, it was unclear what was driving this mortality.

To find out, first author Marije Benedictus and colleagues conceived of the MISTRAL study, short for “do MIcrobleeds predict STRoke in ALzheimer’s" disease. They recruited participants from a memory clinic in Amsterdam who had been diagnosed with AD between 2002 and 2009. They gave each a physical and neurologic examination, and a brain MRI. Out of 5,229 volunteers, 111 people, with an average age of 71, showed evidence of microbleeds in the brain. Benedictus followed up on those patients using data from the Dutch Municipal Population Register, and from the national register, Statistics Netherlands, to see who had died, and how, between 2012 to 2014. She correlated microbleeds with stroke-related deaths and cardiovascular mortality. To see how microhemorrhages related to morbidities and other factors, the researchers sent questionnaires to patients’ physicians asking about incidence of stroke, cardiovascular events, nursing-home placement, and use of antithrombotics—anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs that reduce the formation of blood clots. For comparison, the researchers selected another 222 age- and sex-matched AD patients with no microbleeds for follow-up as well.

While only 38 percent of people in the group without microbleeds died, 56 percent (62 people) from the group with microbleeds passed away. Within the latter group, those who had lobar microbleeds at baseline were likelier to die of stroke or to have experienced a stroke. Though the number of these events was too small to calculate which stroke subtype was responsible, intracerebral hemorrhage seemed to occur more frequently in people with lobar microbleeds, as compared to ischemic stroke. This implied that a higher risk for bleeding could explain the more frequent strokes. On the other hand, patients with non-lobar microbleeds were likelier to die of a cardiovascular-related illness or to suffer a cardiovascular event such as myocardial infarction, heart failure, cardiac arrhythmia, or aortic aneurysm. People with lobar and non-lobar microbleeds had even greater chances of incident stroke and cardiovascular events if they were taking antithrombotic medication. Antithrombotics previously had been found to increase the risk of cerebral microbleeds in elderly people (Jun 2009 news).

All in all, the study confirms the group’s previous finding that microbleeds predict mortality in AD. It further establishes that microbleeds from lobar regions predict stroke, while those in deeper, non-lobar regions predict cardiovascular-related problems in AD patients. A previous study in the general population linked lobar microbleeds with amyloid deposition and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA)—the buildup of Aβ in blood vessels (Vernooij et al., 2008).

That microbleeds predispose for stroke could have implications for trials of Aβ immunotherapy, Iadecola said. A worrisome side effect seen in immunotherapy trials for AD are amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) that indicate leakiness or bleeding in the brain’s blood vessels (July 2011 news). “If these vessels are already damaged, as indicated by the presence of microbleeds, immunotherapy may further increase the vascular risk,” said Iadecola. He suggested paying special attention to these patients during trials to see if and how they differ, and whether they require special doses or treatments. “Amyloid around blood vessels has become a major issue,” agreed Alex Roher, Arizona Alzheimer’s Consortium, Phoenix, saying that the paper supports an association between CAA and microbleeds. “We should investigate the effects of immunotherapy on blood vessels that are loaded with amyloid.” Benedictus noted that they are unsure whether the spontaneously occurring microbleeds are the kind that result from clearing amyloid, but echoed that these trial participants deserve special consideration.

In terms of the risk from antithrombotics, Benedictus was careful not to over-interpret those results. They could suggest that physicians need to balance the lowered risk of ischemic stroke and cerebrovascular disease that comes with these medications, with the possible heightened risk of bleeding, she said—Gwyneth Dickey Zakaib

References

News Citations

- Cause for a Headache: Aspirin May Increase Cerebral Microbleeds

- Paris: Renamed ARIA, Vasogenic Edema Common to Anti-Amyloid Therapy

Paper Citations

- Cordonnier C, van der Flier WM, Sluimer JD, Leys D, Barkhof F, Scheltens P. Prevalence and severity of microbleeds in a memory clinic setting. Neurology. 2006 May 9;66(9):1356-60. PubMed.

- Henneman WJ, Sluimer JD, Cordonnier C, Baak MM, Scheltens P, Barkhof F, van der Flier WM. MRI biomarkers of vascular damage and atrophy predicting mortality in a memory clinic population. Stroke. 2009 Feb;40(2):492-8. PubMed.

- Vernooij MW, van der Lugt A, Ikram MA, Wielopolski PA, Niessen WJ, Hofman A, Krestin GP, Breteler MM. Prevalence and risk factors of cerebral microbleeds: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Neurology. 2008 Apr 1;70(14):1208-14. PubMed.

Further Reading

Papers

- Vernooij MW, van der Lugt A, Ikram MA, Wielopolski PA, Niessen WJ, Hofman A, Krestin GP, Breteler MM. Prevalence and risk factors of cerebral microbleeds: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Neurology. 2008 Apr 1;70(14):1208-14. PubMed.

- Whitwell JL, Kantarci K, Weigand SD, Lundt ES, Gunter JL, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Spychalla AJ, Drubach DA, Petersen RC, Lowe VJ, Jack CR Jr, Josephs KA. Microbleeds in atypical presentations of Alzheimer's disease: a comparison to dementia of the Alzheimer's type. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45(4):1109-17. PubMed.

- Meier IB, Gu Y, Guzaman VA, Wiegman AF, Schupf N, Manly JJ, Luchsinger JA, Viswanathan A, Martinez-Ramirez S, Greenberg SM, Mayeux R, Brickman AM. Lobar microbleeds are associated with a decline in executive functioning in older adults. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;38(5):377-83. Epub 2014 Nov 25 PubMed.

- Kester MI, Goos JD, Teunissen CE, Benedictus MR, Bouwman FH, Wattjes MP, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, van der Flier WM. Associations between cerebral small-vessel disease and Alzheimer disease pathology as measured by cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. JAMA Neurol. 2014 Jul 1;71(7):855-62. PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Benedictus MR, Prins ND, Goos JD, Scheltens P, Barkhof F, van der Flier WM. Microbleeds, Mortality, and Stroke in Alzheimer Disease: The MISTRAL Study. JAMA Neurol. 2015 May;72(5):539-45. PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.