No Hill of Beans: AlzRisk Adds Obesity, Expands Diabetes

Quick Links

Did you ever wonder what all the studies on weight and Alzheimer’s amount to at the end of the day? Thanks to its latest upgrade, AlzRisk can now answer that question. The public database newly features information on obesity, bringing the number of environmental AD risk factors 10. Also new are greatly expanded diabetes content and improved display of meta-analysis and search details. Deborah Blacker of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, and Jennifer Weuve of Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, lead AlzRisk’s curation team.

Hosted by Alzforum, the AlzRisk site launched in 2008 with the aim to make sense of the complicated and sometimes contradictory literature on non-genetic AD risk factors. The AlzRisk team analyzes data from peer-reviewed prospective studies of well-defined cohorts. “This was a lot of work to put together. I think it is a very useful resource,” wrote Kathleen Hayden, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, in an e-mail to Alzforum.

Analysis of the 19 studies selected for AlzRisk’s latest entry, obesity, “strongly suggests that obesity at midlife increases one’s risk of AD,” Weuve said. However, the impact of widening waistlines becomes murkier in older adults. According to the AlzRisk analysis, carrying extra pounds at that age is associated with reduced risk for AD, whereas being underweight in late life appears to increase it. Sunali Goonesekera, a former doctoral student at the Harvard School of Public Health, led the AlzRisk obesity analysis.

What might explain this discrepancy between phases of life? “Part of it could be reverse causation. Perhaps the disease process itself is causing the weight loss,” said Weuve, noting that weight changes can show up five years before AD is diagnosed. Bewildering survival issues can also complicate data interpretation. “If you are morbidly obese, you are less likely to survive to age 70—which means that if we have a fairly obese person in his [or her] seventies, there are probably additional, unknown factors contributing to survival,” Weuve said. Those factors may protect against AD. In addition, data on late-life obesity could be hard to interpret because body-mass index (BMI)—a measurement of body weight in relation to height—may not be the best parameter. “If you take typical people in midlife, lower BMI generally means less body fat,” Weuve said. “However, the older you get, the more dense lean muscle mass you lose, so lower BMI could actually reflect more lean muscle loss.” A detailed discussion of obesity as it relates to AD appears in the AlzRisk entry.

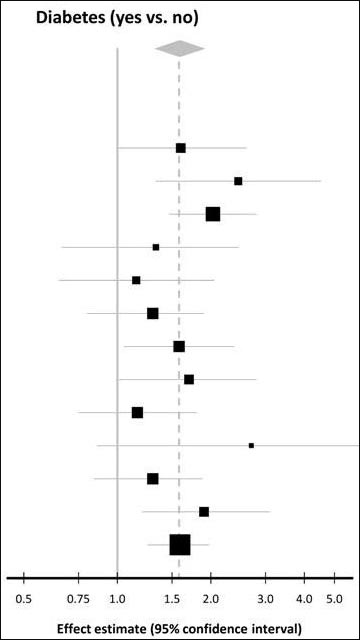

In addition to the new obesity data, AlzRisk expanded its section on diabetes. Previously consisting of one table, the page now has eight new tables comparing requisite data from studies on hyperglycemia, blood glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance. The updated content—led by another HSPH doctoral student, Gautam Sajeev—suggests that not just outright diabetes, but also pre-diabetic states, especially impaired glucose intolerance, may be linked to increased AD risk.

Before crunching numbers and puzzling over what the data mean, the AlzRisk team rigorously selects studies for analysis. For example, it excludes retrospective analyses, animal studies, and studies that did not specifically score for “AD” as opposed to “dementia.” These criteria set a high bar: Of 6,259 obesity citations coming out of the initial electronic search, only 19 made it into the meta-analysis. As part of its recent update, AlzRisk now includes more detail on how it searches the literature for studies on a given putative risk factor. While still applying the same inclusion criteria, the site now documents its search strategies and has flow charts depicting how studies were selected for meta-analysis (see obesity search strategy).

“I find this website much improved,” noted Kristine Yaffe of the University of California, San Francisco. “The inclusion/exclusion criteria and search strategies are essential.” However, she worries they may “miss some important data.” Yaffe suggests expanding to include studies that measure cognitive change or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) outcomes, in addition to those measuring AD. “If we believe there is a continuum, then risk factors for AD should be similar to those for MCI, and one can intervene earlier, perhaps,” Yaffe wrote in an e-mail to Alzforum.

Among other improvements, AlzRisk reformatted its forest plots, which show, at a glance, the overall effect size of the putative risk factor, as well as effect sizes and error margins of the risk factor from individual studies in the meta-analysis. The new plots display information more cleanly and precisely—a shift that brings their style close to that used by AlzGene, a Web-based catalogue of AD genetic association studies (e.g., see meta-analyses of diabetes and BIN1). “The change in appearance is consistent with our aim of presenting the results as clearly as possible and keeping the results up to date as easily as possible,” Weuve said. For readers less savvy in epidemiology, AlzRisk has a glossary that defines terms like “effect size.”

Image courtesy of Jie Shen and Cell Press

The latest AlzRisk changes also include updated meta-analysis and search strategy description for blood pressure and additional search strategy content for head injury.—Esther Landhuis.

References

External Citations

Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.