Lancet Commission Claims a Third of Dementia Cases Are Preventable

Quick Links

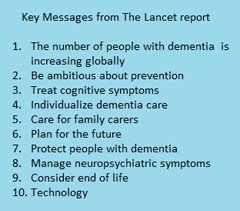

Spurred by the 2013 G8 Dementia Summit in London and by the First WHO Ministerial Conference on Global Action Against Dementia in March 2015, The Lancet commissioned an expert project to review available evidence and recommend how best to manage and prevent dementia. The group’s report, “Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care,” was released to coincide with a symposium on the topic at this year’s Alzheimer’ Association International Conference, held in London July 16-20. The 65-page document, authored by 24 leading dementia researchers from Europe, North America, and Australia, delivers 10 key messages (see box below). Most address patient treatment and care. The one that captured the most attention, especially in the general media, was to “be ambitious about prevention,” since it concluded that a third of dementia cases might be delayed or prevented.

As outlined by Gill Livingston, a psychiatrist at University College London who led the effort, the commission arrived at that number by estimating the population-attributable fraction for a variety of risk factors, even those at play from an early age. “This is the very first life-course analysis of risk factors for dementia,” Livingston stressed in an AAIC press briefing. Livingston captured that life-course in a figure that many at AAIC, including commission member Eric Larson, Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Washington, found compelling (see figure below). “Without sounding hyperbolic, I think this is just brilliant,” Larson told Alzforum. “It shows that the [dementia] condition has its roots throughout the life, which is true for other chronic conditions, such as vascular disease and even cancer,” he said.

Taken from the literature, poor childhood education; midlife hearing loss, hypertension, and obesity; and smoking, depression, physical inactivity, social isolation, and diabetes in late life emerged as modifiable risk factors for dementia. Added together, they accounted for 35 percent of cases, the authors concluded. That compares to only 7 percent of cases attributable to ApoE, the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset AD. The report stresses treating midlife hypertension as an immediately actionable priority for physicians and patients, and claims that controlling the other risk factors would help reduce the number of dementia cases.

Life Course of Dementia Risk.

Starting from childhood, modifiable risk factors add up to 35 percent of dementia cases, according to the report. [Courtesy of Livingston et al., The Lancet 2017.]

In an accompanying comment in The Lancet, Martin Prince, King’s College London, calls the report “a timely evidence-driven contribution to global efforts to improve the lives of people with dementia and their carers, and limit the future impact on societies.” Lancet editors Helen Frankish and Richard Horton called on governments to use the report to help them update action plans for dementia care. Researchers at AAIC welcomed the report but asked what practical effect it will have without a public information campaign to go along with it. Livingston didn’t dismiss such an effort, but noted that evidence is still insufficient to recommend specific interventions to reduce most of the risk.

For her part, Deborah Barnes, University of California, San Francisco, questioned whether the evidence was strong enough to draw causal connections between the risks and dementia. Livingston said that the evidence for causality was stronger for some factors, such as hearing loss, than others. Experts on the commission conceded that randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trials remain the gold standard to prove causality, but for some risk factors, RCTs would be unethical or impractical, e.g., to prove childhood education influences risk for dementia. In the absence of clinical trial data, the commission relied on epidemiological criteria for causality established by Bradford Hill (Hill, 1965). “The standard of evidence is as high as possible for something like childhood education wherein we can’t do randomized controlled trials,” committee member Lon Schneider, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, told Alzforum. He added that treating midlife hypertension in a RCT with cognitive impairment as an end point might be as impractical as doing RCTs of cigarette smoking with lung cancer end points. The report also acknowledged that the incidence of dementia in the developed world has fallen in the last few decades, a trend that researchers have attributed to modifiable risk factors identified in the report, such as healthier lifestyles and reduction in cardiovascular disease (Nov 2016 news; Feb 2016 news).

Beyond prevention, the commission devoted much of the report to recommendations for treatment and care of people who have dementia, and for their caregivers. Led by Livingston, Schneider, and Andrew Sommerlad at UCL, commission members constructed flow charts detailing approaches for managing psychosis, agitation, and depression that clinicians and caregivers may find useful. They offer guidance on dealing with sleep disorders and apathy, as well. In emphasizing the need to protect people with dementia from abuse, the report explains how it likely occurs and outlines approaches to counter it. The report recognizes the difficulties of managing people with end-stage dementia and recommends approaches for palliative care. It also discusses the value of technological advances for care management.

The Lancet report follows on the heels of a similar review from the National Academy of Science Engineering and Medicine that stopped short of issuing guidelines for the general public (Jun 2017 news). Are the two reports at odds? Experts don’t see it that way. The NASEM report also identified physical exercise, cognitive training, and blood pressure management as potential interventions to prevent dementia; however, according to Larson that committee was tasked to review the available evidence, mostly from RCTs, and make recommendations that would satisfy the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. “As such, the standards of evidence the NASEM committee considered had to cross a much higher bar,” he said. Larson served on both the NASEM committee and the Lancet Commission. Ron Petersen, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, agreed. “The NASEM recommendations are consistent with what the Lancet commission says,” he told Alzforum. He also served on the NASEM committee.

Larson, Petersen, and Schneider all emphasized that the Lancet commission report was much broader in scope, tackling everything from prevention to care to public policy. “The NASEM committee just looked at intervention,” noted Petersen, “and while the level of data, and how you interpret it, may be different [between the two reports], the overall message is similar.”—Tom Fagan

References

News Citations

- U.S. Dementia Rates Fall

- Falling Dementia Rates in U.S. and Europe Sharpen Focus on Lifestyle

- Preventing Dementia: Getting Closer to Recommendations

Paper Citations

- HILL AB. THE ENVIRONMENT AND DISEASE: ASSOCIATION OR CAUSATION?. Proc R Soc Med. 1965 May;58:295-300. PubMed.

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Primary Papers

- Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C, Fox N, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Larson EB, Ritchie K, Rockwood K, Sampson EL, Samus Q, Schneider LS, Selbæk G, Teri L, Mukadam N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017 Jul 19; PubMed.

- Prince M. Progress on dementia-leaving no one behind. Lancet. 2017 Jul 19; PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

University of Oxford

The Lancet Commission report is an heroic achievement but it was rather selective in the risk factors that it reported and which formed the basis of the widely-cited claim that more than a third of dementia cases might be prevented if all the modifiable risk factors could be tackled. The Commission omitted to mention raised plasma homocysteine. This risk factor has been identified in many studies, as recently reviewed (McCaddon & Miller, 2015; Smith & Refsum, 2016). For example, a meta-analysis from NIA considered raised homocysteine to be one of the three strongest risk factors, along with low education and decreased physical activity, and estimated that it has a relative risk of 1.93 and a Population Attributable Risk (PAR) of 21.7% (Beydoun et al., 2014). In view of this high PAR, it is therefore likely that if plasma homocysteine could be lowered it would have a significant impact upon dementia incidence. In fact, lowering of homocysteine (by about 30%) is readily achieved by treatment with high doses of B vitamins. Two trials have shown that lowering homocysteine reduces age-related cognitive decline in normal ageing (Durga et al., 2007) and slows both brain atrophy and cognitive decline in people with MCI (VITACOG trial) (de Jager et al., 2012; Douaud et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2010). The effect of B vitamin treatment on people with MCI who have high baseline homocysteine is consistent with a disease-modifying effect (Smith & Refsum, 2017) but trials are needed to demonstrate that this treatment will slow conversion from MCI to dementia.

The Lancet Commission’s omission of high homocysteine as a modifiable risk factor is unfortunate since the treatment (B vitamins) is safe and inexpensive and could significantly benefit people with MCI and would be highly cost-effective (Tsiachristas & Smith, 2016). It was also unfortunate that the Commissions incorrectly reported a paper from the VITACOG trial (de Jager et al., 2012) as showing a lack of effect of B vitamins on global cognition whereas in fact the paper showed a significant slowing of decline in MMSE in those with high homocysteine who were treated with B vitamins.

References

Beydoun, M. A., Beydoun, H. A., Gamaldo, A. A., Teel, A., Zonderman, A. B., & Wang, Y. (2014). Epidemiologic studies of modifiable factors associated with cognition and dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 643. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-643

de Jager, C. A., Oulhaj, A., Jacoby, R., Refsum, H., & Smith, A. D. (2012). Cognitive and clinical outcomes of homocysteine-lowering B-vitamin treatment in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, 27(6), 592-600. doi:10.1002/gps.2758

Douaud, G., Refsum, H., de Jager, C. A., Jacoby, R., Nichols, T. E., Smith, S. M., & Smith, A. D. (2013). Preventing Alzheimer's disease-related gray matter atrophy by B-vitamin treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110(23), 9523-9528. doi:10.1073/pnas.1301816110

Durga, J., van Boxtel, M. P., Schouten, E. G., Kok, F. J., Jolles, J., Katan, M. B., & Verhoef, P. (2007). Effect of 3-year folic acid supplementation on cognitive function in older adults in the FACIT trial: a randomised, double blind, controlled trial. Lancet, 369(9557), 208-216.

McCaddon, A., & Miller, J. W. (2015). Assessing the association between homocysteine and cognition: reflections on Bradford Hill, meta-analyses and causality. Nutr Rev, 73(10), 723-735.

Smith, A. D., & Refsum, H. (2016). Homocysteine, B vitamins, and cognitive impairment. Annu Rev Nutr, 36, 211-239. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-071715-050947

Smith, A. D., & Refsum, H. (2017). Dementia prevention by disease-modification through nutrition. J Prev Alz Dis, in press. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2017.16

Smith, A. D., Smith, S. M., de Jager, C. A., Whitbread, P., Johnston, C., Agacinski, G., . . . Refsum, H. (2010). Homocysteine-lowering by B vitamins slows the rate of accelerated brain atrophy in mild cognitive impairment. A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 5(9), e12244. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012244.

Tsiachristas, A., & Smith, A. D. (2016). B-vitamins are potentially a cost-effective population health strategy to tackle dementia: Too good to be true? Alzheimers Dement (NY), 2, 156-161.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.