As DIAN Wraps Up Anti-Aβ Drug Arms, it Sprouts Tau, Primary Prevention Arms

Quick Links

At the fifth annual DIAD family meeting held July 13 in Los Angeles, Randall Bateman of Washington University, St. Louis, stood before an audience of laypeople who had come from around the world to hear the latest about the grand project to which they have for years been giving hours upon hours taking tests, lying in scanners, giving their blood and cerebrospinal fluid—and a whole lot of good faith. As of 2019, the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network has been continually enrolling and cultivating trust and active engagement of families for a decade. The first secondary prevention trial that grew out of DIAN is coming to a close this year. What’s next, the families wanted to know?

- Solanezumab and gantenerumab secondary prevention trials coming to a close this year.

- Two new trials are starting a cognitive run-in phase this year.

- Drug selection still ongoing for first primary prevention trial, of people 18 and older.

The family conference was but one DIAN event around the Alzheimer’s Association International conference, held July 14–18. There were closed meetings of the DIAN observational study’s (DIAN-Obs) steering committee, of its trials unit (DIAN-TU), plus a dozen scientific talks and posters on DIAN data scattered throughout the AAIC conference itself. Even so, addressing the people whose family devastation Bateman and WashU’s John Morris set out to solve was key to keep the movement energized and maintain both recruitment of new people and retention of current members, despite the great effort and time involved.

To do that, Bateman laid out what lies ahead in clinical trials, and WashU’s Eric McDade worked with the 20- and 30-year-olds in the room in search of solutions for a primary prevention trial.

The initiative’s observational cohort and trials unit are separately funded, but integrated, projects. People who are in DIAN-Obs can transition into DIAN-TU when a treatment trial whose inclusion criteria they meet becomes available. DIAN-Obs, currently 562 people strong, works to recruit some 25 new members annually to compensate for attrition into TU or to advancing disease. DIAN-Obs has upgraded its procedures and data storage to meet good clinical practice and Code of Federal Regulations/FDA guidelines on electronic records, so that its samples can be transferred seamlessly and its data merged with those of DIAN-TU. The TU is tapping Obs for external control data, effectively increasing its placebo pool, whereas Obs is using TU placebo data to increase its sample size for progression studies.

DIAN-TU currently operates at 27 sites in eight countries, whereas DIAN-Obs operates at 19 sites, with Barcelona starting this fall. For example, Canada currently has four DIAN-TU sites but had no DIAN-Obs sites until now; McGill University in Montreal will soon start enrolling into DIAN-Obs. This difference reflects a lack of local funding for more DIAN-Obs sites. It also followed a realization DIAN leaders made when they increased outreach into additional countries. This brought forward many more families and their local neurologists than were known to exist at the start in 2008. Many of the newly found families, it turned out, were not ready to join DIAN-Obs, but did want treatment trials. Sixteen future DIAN-TU sites in Argentina, Brazil, China, Colombia, Japan, and Mexico are pending; three sites in the Netherlands and Germany are still facing some delays.

Since DIAN-Obs began, its research has defined the stages of Alzheimer’s disease beginning 20 years prior to symptom onset, and shown the order—at least as detectable with currently available markers—to be amyloid, tau, metabolism, brain shrinkage, memory loss, and dementia. DIAN received 235 data and tissue requests, fulfilled 80 percent of them, and 150 papers have been published with DIAN data. Starting in 2012, DIAN-TU, along with its sister project, the Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative’s Colombia initiative, began the first AD prevention trials using anti-amyloid drugs and the first trials specifically for people with dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease.

Both DIAN and API have built a registry-driven platform to support a continual series of investigational drug trials that adapt as new research findings come out, for example by changing the dose, adding new biomarkers, and developing statistics suitable to their particular cohorts.

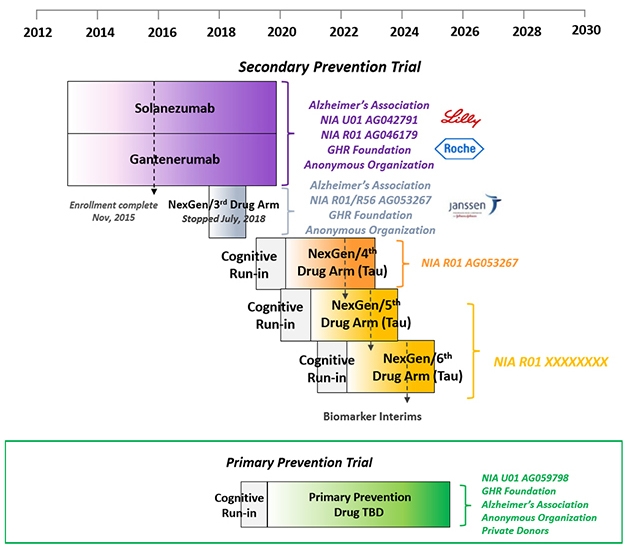

Having broadly defined stages of proteinopathy in autosomal-dominant AD, DIAN is set to conduct an ongoing series of primary and secondary prevention trials as participants, drugs, and funds become available. [Courtesy of DIAN-TU.]

The first two secondary prevention trials—of the anti-Aβ antibodies solanezumab and gantenerumab—will each see their last patient at the end of this year. Among themselves, DIAN participants are chatting about how to mark their last visit, and the nervous wait for the result after that. “Collecting and cleaning the data has started, and in 2020 we will work around the clock to analyze it,” Bateman told the audience in L.A., who included a fair number of participants in those two drug arms. “Once that is done, a group of people will be locked in a room and learn the results. Within 24 hours of that we will make an announcement to you and the world,” Bateman said.

DIAN-TU prevention trials platform. [Courtesy of DIAN-TU.]

(The third DIAN-TU drug arm, of the BACE inhibitor atabecestat, stopped in 2018 when its sponsor, Janssen, suspected liver toxicity. Indeed, at the AAIC conference in Los Angeles, David Henley of Janssen reported that further analyses of data from its other atabecestat trial in late-onset AD reinforced the decision to stop because atabecestat had worsened cognition slightly in people with very mild symptoms, as had other BACE inhibitors before it.)

What happens once the solanezumab and gantenerumab results are out, DIAN members want to know? If these two antibodies did not help, the trials stop and DIAN participants can consider the next trial, arm 4. If either worked, then its participants can join an open-label extension that will start next summer. One wrinkle here is that people will have to find out their mutation status at that point. Up to that point, they did not, because noncarriers were randomized to placebo. With open-label, however, noncarriers would expose themselves to side effects of a drug they do not need. Bateman recommended genetic counseling and testing after the placebo-controlled period, but only if a drug has proven effective, and said that DIAN will provide these services.

What about the next trials? Earlier this year, a cognitive run-in portion started for the fourth attempt at secondary prevention in people who have Alzheimer’s pathology but no symptoms. Ditto for a primary prevention trial in younger people who have no AD pathology yet. This run-in serves as a way for scientists and participants to get going now and strengthen the dataset with biomarker and progression data on each participant, even before a drug has been chosen. DIAN participants who are entering the fourth secondary prevention arm will have a tau PET scan as part of their run-in, as well.

Which drugs are right for the next trials? This pressing question is being debated behind closed doors. In L.A., DIAN scientists were not ready to say, except that the fourth trial will most likely test an anti-tau drug. Throughout the AD research field, calls for targeting tau therapeutically have been growing, though the first setbacks are starting, as well (Jul 2019 news). Recent PET data has shown that neurofibrillary tangles come up fast in familial AD around the time a person shows symptoms. This has given DIAN-TU researchers hope that tau PET scans will show them sooner than amyloid scans do whether a drug against tau has reached and reduced its target—and staves off symptoms. Curiously, tangles appear to spread differently in familial than sporadic AD; with a heavy presence in the back of the brain.

Tau PET scans suggest that neurofibrillary tangles form in the brain when a person with dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s becomes symptomatic, coming up faster and with a heavier burden in the back of the brain than in LOAD. [Courtesy of Benzinger et al., WashU.]

DIAN researchers believe that a big therapeutic effect is likely going to require hitting both Aβ and tau. Given that a handful of tau-targeting antibodies and other drugs, see below, have entered Phases 1 and 2 in LOAD, DIAN-TU is planning to evaluate three such drugs in the next five years in hopes of finding a winner for future combination trials. Drug arms 5 and 6, just like arm 4, will test a different tau drug in one- to two-year Phase 2 biomarker studies enrolling 70 people per trial. The best one will go forward into a Phase 3 trial that uses a cognitive endpoint and could support FDA approval, Bateman said. Funding for arm 4 is in hand, a grant proposal for arms 5 and 6 on track for submission this November. Bateman noted that unlike for arms 1 to 3, which were funded primarily by pharma, funding for arm 4 comes mostly from public and philanthropic sources, to afford the DIAN-TU drug evaluation committee full independence in their choice. Those funders include the Alzheimer’s Association, the GHR Foundation, and an anonymous organization.

The primary prevention trial, aka PPT, was widely assumed to evaluate a BACE inhibitor. Alas, CNP520, the Novartis drug being evaluated in a large Phase 3 secondary prevention program with API, stumbled over cognitive side effects earlier this month (Jul 2019 news). This latest downfall of another BACE inhibitor cast a pall over the future of the entire drug class. “This places great concern on anyone’s further use of BACE inhibitors,” Bateman said. One such inhibitor, elenbecestat, remains on track.

At AAIC, the prevailing outlook among most researchers about the prospects of BACE inhibitors was highly skeptical. That said, the cognitive decline seen at higher doses than would be used in primary prevention was small and did not worsen over time. Ease of use is an important consideration for a trial that runs for four to six years, and most antibodies require repeated infusion or injection, whereas BACE inhibitors come as pills. DIAN scientists are mulling whether a much lower dose of a BACE inhibitor is still an option, and until that is done, they are staying mum about which drug will go into the PPT.

This trial is a crown jewel at DIAN-TU, since it offers the purest test of the amyloid hypotheses attempted to date (Aug 2017 conference news). Last fall it received a large grant from the NIA and, subsequently, marching orders from the FDA. It aims to compare a drug to placebo in as many people as are necessary to enroll until 160 mutation carriers are on board. The precise number is unknown because genetic testing is not required to join. The blinded treatment phase will last for four years, with full site visits every two years, and short visits and frequent phone check-ins in between. Stopping amyloid accumulation is the primary goal. If the study drug does that, then all participants can go on open-label treatment for another two years, though again, at this point at-risk people would have to learn their mutation status.

This study faces unique design challenges. It invites all young adults at risk of a DIAD mutation, whether they know their genetic status or not, up until 15 years prior to their family’s age at onset. For example, if dad became symptomatic at 49, his children between 18 and 34 are eligible for the primary prevention trial (older children can join a DIAN-TU secondary prevention trial). The problem? Because exposing a fetus, or even sperm, to investigational medications is unacceptable, PPT participants must forgo pregnancy while they are on study medication, i.e., during their prime childbearing years—and half of them would do so while taking a placebo.

“We have been hearing from you that this is a serious issue,” McDade told the audience. To address it, McDade live-polled young adults at the family conference via an app to gauge what they would support.

In summary, four in five at-risk young people in the room indicated that they were willing to forgo pregnancy for the duration of the trial. Of the ones who were not, most said they would enroll if they could take a break after the four-year blinded phase. Conceivably, people could be in the trial, then get pregnant and go on open-label after the baby is born. Some people indicated they would prefer a “pregnancy break” after two years in the trial.

A quarter of the potential participants in the room had already considered family planning options such as freezing eggs for in vitro fertilization after the trial is over. Most indicated they would be interested in egg freezing, especially if the study was able to cover the expense. Lindsay, the 23-year-old daughter of a DIAN solanezumab trial participant, had told the audience earlier in the day how she had gone about egg freezing, and was mingling with other young people afterward (see Part 1 of this series). Most potential participants also endorsed meeting with a genetic and reproductive counselor as part of joining this trial.—Gabrielle Strobel

References

News Citations

- AbbVie’s Tau Antibody Flops in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

- Cognitive Decline Trips Up API Trials of BACE Inhibitor

- Planning the First Primary Prevention Trial for Alzheimer’s Disease

Therapeutics Citations

Other Citations

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.