Alzheimer’s GWAS Hits Point to Endosomes, Synapses

Quick Links

In taking a closer look at the Alzheimer’s risk genes enlisted by genome-wide association studies, researchers at this year’s Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, held October 17-21 in Chicago, showed off what confocal and super-resolution microscopy have revealed thus far. They spotted Bin1 and CD2AP in endosomes, and Bin1 in postsynaptic compartments as well. The sightings suggest that both Bin1 and CD2AP regulate processing of the amyloid precursor protein, and that Bin1 also regulates insertion of glutamate receptors into dendritic spines. The work helps scientists better understand how GWAS variants in these genes modify risk for AD (see also Part 5 of this series).

Genetic variants near the Bin1 and CD2AP genes increase risk for AD by about 10 to 15 percent, but researchers know little about the basic biology of these two proteins. Bin1 protein is implicated in endosome recycling. Some prior evidence suggested it might modulate tau, but at SfN, Florent Ubelmann, a postdoc in the lab of Claudia Almeida at CEDOC, NOVA Medical School in Lisbon, Portugal, claimed that Bin1 regulates BACE1 trafficking in axons. In parallel experiments, Ubelmann reported that CD2AP, a modulator of the axon cytoskeleton, helps recycle APP in dendrites. The upshot: Loss of either Bin1 or CD2AP leads to increased production of Aβ.

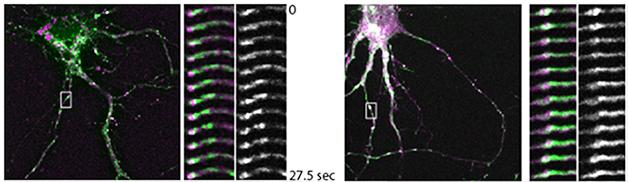

Ubelmann came to these conclusions after knocking down either protein in mouse wild-type neurons. Aβ ticked up in the axons in the Bin1 knockdowns, while more Aβ dotted dendrites when he silenced CD2AP. To find out why, Ubelmann measured protein trafficking with fluorescent pulse-chase experiments. When he silenced Bin1, BACE1 co-localized more with the early endosome marker Rab5 in axons. The secretase exited much more slowly than normal from endosome tubules, where protein sorting occurs (see image below). APP trafficking was unaffected.

Slow BACE. In wild-type neurons (left), BACE1 (green) exits Rab5-labelled endosomes (purple) within about 30 seconds. Knocking down BIN1 stalls the process (right). [Image courtesy of Claudia Almeida.]

Ubelmann saw something different when he knocked down CD2AP. In these cells BACE1 trafficking appeared normal but, in dendrites, endocytosed APP co-localized more with EEA1, a docking protein on the surface of early endosomes. APP seemed to never quite reach the endosome lumen, which is necessary for its degradation (see image below). Almeida told Alzforum that knocking down either Bin1 or CD2AP increases the chances that APP and BACE1 will cross paths as they traffic through endosomes, leading to enhanced processing of APP.

Out of the Loop. Silencing CD2AP (right) keeps APP (red) out of endosomes (green). [Image Courtesy of Claudia Almeida.]

Researchers at the meeting were impressed by the data but noted that much more needs to be done to understand how the GWAS variants increase risk for AD. The CD2AP data seemed to fit with a recent paper from Fan Liao in David Holtzman’s group at Washington University, St. Louis, showing that N2A cells expressing human APP made slightly more Aβ when CD2AP was silenced. “In this respect, Ubelmann’s data matches what we saw,” Liao told Alzforum. It also fits with an increased plaque burden seen in AD patients carrying the CD2AP risk allele (see Shulman et al., 2013). However, Liao found no change in Aβ pathology when she crossed CD2AP heterozygous nulls with APP/PS1 mice, suggesting that any genetic variation would have to reduce CD2AP levels by more than half to influence pathology. In vivo, microglial CD2AP complicates the picture, since it may influence clearance of Aβ.

Some questioned the relevance of the Bin1 data, since recent work seems to suggest levels of the protein correlate tightly with neurofibrillary tangles in the AD brain and not with amyloid plaques (see Holler et al., 2014). Gopal Thinakaran of the University of Chicago works on BACE trafficking. He told Alzforum that interpreting trafficking experiments can be tricky, as any perturbation to the system can have ripple effects. Thinakaran noted that Ubelmann has not yet shown that Bin1 actually functions in axonal endosomes.

And indeed, in a separate SfN nanosymposium, Britta Schurmann, working with Peter Penzes at Northwestern University, Chicago, painted a slightly different picture of Bin1. Using high-resolution structured illumination microscopy (SIM), Schurmann spotted the protein in the postsynaptic compartment, where it co-localized with the GluA1 AMPA glutamate receptor subunit. This did not surprise Almeida, who told Alzforum that Bin1 likely exists in many cellular compartments.

What does Bin1 do in the postsynapse? Schurmann suggested that it regulates spine morphology. Knocking down the protein in primary cortical rodent neurons, she found fewer GluA1 subunits in dendritic spines and smaller spines. Currents evoked from the neurons were weaker than those from normal neurons. Using SIM to hunt for potential interactions suggested by prior in silico analysis, Schurmann found that Bin1 and the endosome markers Rab11 and Arf6 interact. Silencing Bin1 reduced Arf6 and GluA1 in dendritic spine heads, and Schurmann correlated levels of all three proteins with spine area. She concluded that Bin1 may be a cargo adaptor for GluA1. This could make it important for synaptic plasticity, and its role as an AD risk factor could come to bear via that process, Schurmann suggests.—Tom Fagan

References

News Citations

Alzpedia Citations

Paper Citations

- Shulman JM, Chen K, Keenan BT, Chibnik LB, Fleisher A, Thiyyagura P, Roontiva A, McCabe C, Patsopoulos NA, Corneveaux JJ, Yu L, Huentelman MJ, Evans DA, Schneider JA, Reiman EM, De Jager PL, Bennett DA. Genetic susceptibility for Alzheimer disease neuritic plaque pathology. JAMA Neurol. 2013 Sep 1;70(9):1150-7. PubMed.

- Holler CJ, Davis PR, Beckett TL, Platt TL, Webb RL, Head E, Murphy MP. Bridging integrator 1 (BIN1) protein expression increases in the Alzheimer's disease brain and correlates with neurofibrillary tangle pathology. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(4):1221-7. PubMed.

Further Reading

Papers

- Glennon EB, Whitehouse IJ, Miners JS, Kehoe PG, Love S, Kellett KA, Hooper NM. BIN1 is decreased in sporadic but not familial Alzheimer's disease or in aging. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e78806. Epub 2013 Oct 21 PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.