Clearing Aggregates—Macrophages Fall Short for Aβ, but Vaccine Mops Up α-synuclein

Quick Links

Depending on how you look at it, the brain-residing activated microglia observed in Alzheimer disease could be the good guys, clearing amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregates, or the bad guys, promoting inflammation (see ARF related news story and ARF news story). But new results make it clear that good or bad, microglia are not the only guys going after Aβ. In a paper scheduled for publication in the June Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, Milan Fiala and colleagues at UCLA show that macrophages originating from the blood can enter the brain and gobble up amyloid peptides. Intriguingly, macrophages isolated from the blood of AD patients are less effective at clearing Aβ than those from unaffected individuals. The results suggest that controlling Aβ levels involves a systemic immune response, one that may be out of whack in AD patients.

But while macrophages or microglia are pros at vacuuming up and disposing of extracellular neurotoxic deposits like amyloid, what chance does the immune system have against intracellular foes like mutant α-synuclein, which causes Parkinson disease? A fighting chance, as it turns out. Eliezer Masliah, of the University of California in San Diego, Dale Schenk, of Elan Pharmaceuticals, and their colleagues report in today’s Neuron that antibodies to α-synuclein enhance clearance of the protein in transgenic mice expressing human α-synuclein. The vaccine also protects the mice against synaptic loss.

For Fiala and colleagues, the starting point was their previous work showing that macrophages can enter the brain through breaks in the blood-brain barrier. They found, using autopsy tissue, that macrophages infiltrate Aβ plaques, and contain phagocytosed Aβ (Fiala et al., 2002). From these results, they hypothesized that the build-up of Aβ in AD might result from failure of the innate immune system to clear the protein. In the new study, they demonstrated that macrophage infiltration of the frontal lobe and hippocampus occurred in sites where neurons were expressing the chemokines RANTES and IL-1β, but they saw no correlation between the number of macrophages in an area and the plaque burden. This made the researchers wonder if the macrophages in AD brains might be deficient at clearing Aβ.

To answer this question, they isolated monocytes from blood samples from 17 living AD patients and 16 age-matched controls. When the investigators cultured peripheral blood cells from healthy subjects with Aβ, the monocytes stained brightly for the peptide, while cells from AD subjects showed significantly lower staining. After 1 to 3 weeks in culture, the normal monocytes differentiated to macrophages and showed a strong uptake of Aβ into vacuoles resembling lysosomes, followed by clearance of the peptide. In contrast, cells from AD patients exposed to Aβ showed some surface staining only, followed by cell rounding and apoptosis.

This apparent defect in innate immune function in AD subjects was accompanied by increased expression of markers of systemic immune activation, including HLA-DR and COX2, in blood neutrophils. In a smaller sample of five AD subjects and eight controls, Fiala et al. showed that T cell cytokines were also dysregulated. Levels of IL-10, a potent inhibitor of macrophage function, were increased, for example.

The authors conclude that Aβ clearance from brain is not solely the job of microglia—macrophages recruited from the periphery also participate. Their model suggests the macrophages (and perhaps also microglia) can be the good guys and the bad guys. “In normal subjects, monocytes/macrophages (MMs) migrate and phagocytize Aβ at a physiological pace and thus forestall accumulation of Aβ. Thus, physiological innate and adaptive immune responses to Aβ are beneficial in clearance of Aβ, but, in pathological states either due to overproduction of Aβ (familial AD) or deficiency of Aβ clearance (sporadic AD), the detrimental effects and lack of beneficial effects tilt the balance to neuronal pathology,” they write. The failure of AD macrophages to clear Aβ would also contribute to tipping the balance toward harmful inflammation.

Efforts to rally the immune system via immunization to clear Aβ have stimulated efforts to develop vaccines against other neurodegenerative diseases. The latest attempt finds Masliah and colleagues challenging mice transgenic for human α-synuclein with a recombinant α-synuclein vaccine. The mice gave robust antibody response, and showed a reduction in synuclein-containing inclusion bodies in the temporal cortex. Immunization decreased α-synuclein levels in presynaptic nerve terminals, and reversed the loss of synaptophysin-labeled nerve terminals that occurs in synuclein transgenic mice.

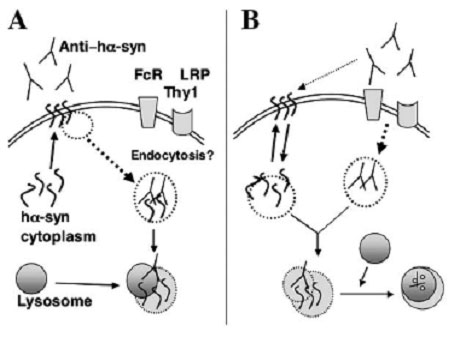

Two possible mechanisms for antibody-mediated neutralization of cytosolic proteins

In one (A), enough of the cytosolic protein is present at the surface of the cell to bind circulating antibody. The antigen-antibody complex is then degraded following uptake by lysosomes. In the second (B), the antibody is first internalized via cell surface receptors, then binds to the cytosolic protein and carries it to the lysosomes for degradation. [Image courtesy of Masliah et al. 2005/Neuron]

It’s easy to picture how immunization can result in the clearance of extracellular proteins like Aβ, but how does it work on synuclein, a predominantly intracellular protein? Under pathologic conditions, it turns out, oligomers and protofibrils of synuclein are found in the membrane (see for example Dixon et al., 2005 and Eliezer et al., 2001). The researchers showed that the vaccine-elicited antibodies reduced membrane-localized aggregated synuclein, probably by targeting it for lysosomal degradation. The disappearance of synuclein did not seem to involve uptake by other immune cells, since they saw no sign of infiltration by lymphocytes and only mild microglial activation after immunization. The immunized mice showed only a mild inflammatory response to the vaccine, the same as adjuvant controls. These results, together with a recent report of a DNA vaccine strategy to hit the huntingtin protein (Miller et al., 2003) suggest that immunotherapy could be widely applicable to a growing range of neurodegenerative diseases.—Pat McCaffrey.

References:

Fiala M, Lin J, Ringman J, Kermani-Arab V, Tsao G, Patel A, Lossinsky AS, Graves MC, Gustavson A Sayre J, Sofroni E, Suarez T, Chiapelli F, Bernard G. Ineffective phagocytosis of amyloid-beta by macrophages of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2005 June;7:221-232. Abstract

Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Adame A, Alford M, Crews L, Hashimoto M, Suebert P, Lee M, Goldstein J, Chilcote T, Games D, Schenk, D. Effects of alpha-synuclein immunization in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2005 June 16;46:857-868. Abstract

References

News Citations

- Glia—Pictures from an Exposition

- St. Moritz: Part 5. Vaccine, Microglia, NGF News Fill in Neuroimmunology Picture

Paper Citations

- Fiala M, Liu QN, Sayre J, Pop V, Brahmandam V, Graves MC, Vinters HV. Cyclooxygenase-2-positive macrophages infiltrate the Alzheimer's disease brain and damage the blood-brain barrier. Eur J Clin Invest. 2002 May;32(5):360-71. PubMed.

- Dixon C, Mathias N, Zweig RM, Davis DA, Gross DS. Alpha-synuclein targets the plasma membrane via the secretory pathway and induces toxicity in yeast. Genetics. 2005 May;170(1):47-59. PubMed.

- Eliezer D, Kutluay E, Bussell R, Browne G. Conformational properties of alpha-synuclein in its free and lipid-associated states. J Mol Biol. 2001 Apr 6;307(4):1061-73. PubMed.

- Miller TW, Shirley TL, Wolfgang WJ, Kang X, Messer A. DNA vaccination against mutant huntingtin ameliorates the HDR6/2 diabetic phenotype. Mol Ther. 2003 May;7(5 Pt 1):572-9. PubMed.

- Fiala M, Lin J, Ringman J, Kermani-Arab V, Tsao G, Patel A, Lossinsky AS, Graves MC, Gustavson A, Sayre J, Sofroni E, Suarez T, Chiappelli F, Bernard G. Ineffective phagocytosis of amyloid-beta by macrophages of Alzheimer's disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005 Jun;7(3):221-32; discussion 255-62. PubMed.

- Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Adame A, Alford M, Crews L, Hashimoto M, Seubert P, Lee M, Goldstein J, Chilcote T, Games D, Schenk D. Effects of alpha-synuclein immunization in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2005 Jun 16;46(6):857-68. PubMed.

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Primary Papers

- Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Adame A, Alford M, Crews L, Hashimoto M, Seubert P, Lee M, Goldstein J, Chilcote T, Games D, Schenk D. Effects of alpha-synuclein immunization in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2005 Jun 16;46(6):857-68. PubMed.

- Fiala M, Lin J, Ringman J, Kermani-Arab V, Tsao G, Patel A, Lossinsky AS, Graves MC, Gustavson A, Sayre J, Sofroni E, Suarez T, Chiappelli F, Bernard G. Ineffective phagocytosis of amyloid-beta by macrophages of Alzheimer's disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005 Jun;7(3):221-32; discussion 255-62. PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

National Institute on Aging

It seems increasingly likely that α-synuclein is central to the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease and diffuse Lewy body disease. Therefore, strategies like the one outlined in this paper to decrease α-synuclein protein levels may be viable options for therapeutics in the future. Other labs have reported different approaches to the same problem, such as recombinant intrabodies (Emadi et al., 2004), anti-aggregating peptides (El-Agnaf et al., 2004), or overexpression of β-synuclein (Hashimoto et al., 2004). Where the current paper is especially significant is that the major species decreased by this immunization strategy is aggregated forms of the protein. Although this is very hard to quantify, in figure 5 the amount of monomer is left relatively unchanged where oligomers are decreased. This observation provides us with a way to test the idea that relatively soluble aggregates are the major toxic species. What isn’t included in this paper is a test of whether there is a functional decrease in damage resulting from synuclein aggregation, which would be the best predictor of efficacy in humans. Some of the viral models of α-synuclein expression (Lo Bianco et al., 2002; Kirik et al., 2003) have additional measures such as TH cell loss. It will be interesting to see if this peripheral immunization with recombinant synuclein can slow TH cell loss or behavioral outcomes (which are mild so far in many of these models).

There will inevitably be questions about how the antibodies are effective against an intracellular protein, which is very different from the previous reports of immunization against extracellular amyloid plaques. We can be certain that there will be several future studies aimed to define the mechanism, but this is more than an academic argument. The various models posited by Masliah et al. seem to require that there is a small amount of the antigen available to antibodies on the surface of the neuron. Whilst this is true for synuclein, to my knowledge it is not true for other intracellular proteins that aggregate. For these proteins, we may need additional approaches to really get at the aggregation within a neuron. This may be a difficult process, but I think it’s worth trying to jump over the hurdles and get to the point where we can really address whether protein aggregation is central to neurodegeneration—and how to prevent it.

References:

Emadi S, Liu R, Yuan B, Schulz P, McAllister C, Lyubchenko Y, Messer A, Sierks MR. Inhibiting aggregation of alpha-synuclein with human single chain antibody fragments. Biochemistry. 2004 Mar 16;43(10):2871-8. PubMed.

El-Agnaf OM, Paleologou KE, Greer B, Abogrein AM, King JE, Salem SA, Fullwood NJ, Benson FE, Hewitt R, Ford KJ, Martin FL, Harriott P, Cookson MR, Allsop D. A strategy for designing inhibitors of alpha-synuclein aggregation and toxicity as a novel treatment for Parkinson's disease and related disorders. FASEB J. 2004 Aug;18(11):1315-7. PubMed.

Lo Bianco C, Ridet JL, Schneider BL, Deglon N, Aebischer P. alpha -Synucleinopathy and selective dopaminergic neuron loss in a rat lentiviral-based model of Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Aug 6;99(16):10813-8. PubMed.

Kirik D, Annett LE, Burger C, Muzyczka N, Mandel RJ, Björklund A. Nigrostriatal alpha-synucleinopathy induced by viral vector-mediated overexpression of human alpha-synuclein: a new primate model of Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Mar 4;100(5):2884-9. Epub 2003 Feb 24 PubMed.

View all comments by Mark CooksonThe Institute for Molecular Medicine

α-synuclein is a soluble protein that is highly enriched in the presynaptic terminals of neurons in the central nervous system (Iwai A et al., 1995), and it may play a central role in the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease (PD) (Polymeropoulos et al., 1997; Singleton et al., 2003). It is not clear what initiates the production of this native protein, nor is it known by which mechanism α-synuclein can induce neurodegenerative disease. Trojanowski and colleagues (Trojanowski and Lee, 1998; Trojanowski et al., 1998) have suggested that accumulation of oligomeric forms of α-synuclein and/or bigger aggregates in the synaptic terminals and axons may be neurotoxic. Using a Drosophila model of PD, Chen et al. recently demonstrated that phosphorylation of α-synuclein controls neurotoxicity and inclusion body formation. These authors suggested that inclusion bodies are protective, because their increased numbers correlated with reduction of toxicity.

Several therapeutic strategies are currently being investigated for PD, including the administration of neurotrophic factors and transplantation of dopaminergic cells. In the current issue of Neuron, Masliah et al. have used an immunotherapeutic approach to reduce the levels of human α-synuclein in the brains of transgenic mice or to block the assembly of this protein into potentially pathological forms. For immunization, the authors used 3- and 6-month-old heterozygous transgenic mice (Line D) that express human α-synuclein and display abnormal accumulation of insoluble α-synuclein in the brain. When allowed to age, these animals mimic certain aspects of PD, such as motor and neurodegenerative deficits. Masliah et al. used eight injections of 8 μg each of recombinant bacterial α-synuclein first in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) (first injection) and then in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) (second immunization) or in phosphate buffered saline (all subsequent administrations) to induce low titers of anti-α-synuclein antibodies in both groups of experimental mice (detected by ELISA). Such low titers of antibodies are not surprising, since α-synuclein is a self-antigen in the transgenic mice used in these experiments. Using overlapping peptides, the authors next demonstrated that anti-α-synuclein antibodies recognized amino acids 85-99, 109-123, 112-126, and 126-138 of human α-synuclein. Although mice responded quite differently to immunizations, antisera with relatively low and high titers of antibodies have been specific to brain homogenates, neurons, presynaptic terminals, and intraneuronal inclusions. More importantly, the immunizations reduced α-synuclein accumulation, and the antibody titers correlated with reductions in accumulation of neuronal α-synuclein. Successful vaccination also preserved synaptic density without inducing neuroinflammatory responses. However, it should be mentioned that active immunizations with fibrillar Aβ42 did not induce inflammation in any of the mouse models of Alzheimer disease (AD), as well, but inflammation was detected in AD patients that received the AN-1792 vaccine containing human Aβ42.

To further characterize the effects of the immunizations, the authors analyzed the levels of synaptophysin, a 38-kDa calcium-binding glycoprotein that is present in the presynaptic vesicles of neurons and in the neurosecretory granules of neuroendocrine cells in vaccinated and/or CFA injected mice. In the CFA injected transgenic mice, the levels of synaptophysin were reduced, but vaccinated and non-transgenic mice had similar levels of this protein. The authors also analyzed the potential therapeutic mechanism of anti-α-synuclein antibodies in vivo and demonstrated that this antibody bound to α-synuclein associated with neuronal membranes and promoted the degeneration of α-synuclein aggregates. The same data were generated with purified and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-tagged antibodies. This allowed authors to propose that the antibodies generated after active immunizations recognized aggregates of α-synuclein that are associated with the neuronal membrane and/or bound, for example, via Fc-receptors, to proteins on the cell surface, were internalized, and thus could be targeted, along with the antigen, to the lysosomal pathways. Unfortunately, the authors did not analyze the isotype of the antibodies, so it is difficult to discuss the possibility of their binding to FcR. In addition, it is still not clear how antibodies in lysosomes can promote degradation of α-synuclein in this compartment. In fact, it is difficult to explain the clearance of any intracellular endogenous protein by extracellular antibodies. Further studies are required to understand such mechanisms.

Another important question is whether there is an inflammatory response to α-synuclein immunizations. As mentioned above, there were no reports of any adverse autoimmune or inflammatory responses in peripheral tissues or in the brains of APP/Tg mice, a model for AD, after immunization with fibrillar Aβ42. The only adverse event observed was the increased incidence of cerebral microhemorrhage detected in very old APP/Tg mice injected with high levels of anti-Aβ monoclonal antibodies. However, there were no documented reports of APP/Tg mice developing cerebral hemorrhages in response to active immunization with fibrillar Aβ42. Despite impressive preclinical results, Aβ-immunotherapy of AD patients was halted because a small group of vaccinated patients developed meningoencephalitis. Presently, the actual cause of the adverse effects of active immunization with the AN-1792 vaccine is not known, but importantly, the antibody response to Aβ did not correlate with the presence or severity of the symptoms. In fact, some of the patients that developed meningoencephalitis did not have detectable levels of antibodies specific to Aβ peptide, suggesting that the adverse reaction to Aβ-immunotherapy was not due to the humoral antibody response, but rather to a cell-mediated immune response stimulated by AN-1792. The prominent T cell infiltration documented in two case reports currently available from the clinical trial strongly suggest that the sub-acute meningoencephalitis was caused by autoreactive anti-Aβ CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cells. Unfortunately, information on the cytokine profiles in the affected patients has not yet been published. This is unfortunate, because Th1 cytokines (Il12, IL18, IFNγ) have been implicated in many autoimmune disorders, whereas Th2-type responses (IL-4, IL-10, and TGFβ) attenuate cell-mediated immunity and inhibit autoimmune disease.

In this first α-synuclein-immunotherapy, study analyses of Th1 and Th2, cell responses were not included, though these could help us better understand the potency of this vaccine approach for humans. Even the detection of IgG1 and IgG2a isotypes, for example, could help distinguish between a Th1- or Th2-type of humoral immune response.

However, it is clear that the data generated by scientists from the University of California, San Diego, and Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc. will stimulate further preclinical trials with α-synuclein immunogens in different animal models and perhaps even clinical trials in PD patients. Such studies will also allow us to better understand the antibody-mediated α-synuclein clearance mechanisms and how these relate to the pathology of PD.

References:

Iwai A, Masliah E, Yoshimoto M, Ge N, Flanagan L, de Silva HA, Kittel A, Saitoh T. The precursor protein of non-A beta component of Alzheimer's disease amyloid is a presynaptic protein of the central nervous system. Neuron. 1995 Feb;14(2):467-75. PubMed.

Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A, Pike B, Root H, Rubenstein J, Boyer R, Stenroos ES, Chandrasekharappa S, Athanassiadou A, Papapetropoulos T, Johnson WG, Lazzarini AM, Duvoisin RC, Di Iorio G, Golbe LI, Nussbaum RL. Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson's disease. Science. 1997 Jun 27;276(5321):2045-7. PubMed.

Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Peuralinna T, Dutra A, Nussbaum R, Lincoln S, Crawley A, Hanson M, Maraganore D, Adler C, Cookson MR, Muenter M, Baptista M, Miller D, Blancato J, Hardy J, Gwinn-Hardy K. alpha-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson's disease. Science. 2003 Oct 31;302(5646):841. PubMed.

Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Aggregation of neurofilament and alpha-synuclein proteins in Lewy bodies: implications for the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease and Lewy body dementia. Arch Neurol. 1998 Feb;55(2):151-2. PubMed.

Trojanowski JQ, Goedert M, Iwatsubo T, Lee VM. Fatal attractions: abnormal protein aggregation and neuron death in Parkinson's disease and Lewy body dementia. Cell Death Differ. 1998 Oct;5(10):832-7. PubMed.

Chen L, Feany MB. Alpha-synuclein phosphorylation controls neurotoxicity and inclusion formation in a Drosophila model of Parkinson disease. Nat Neurosci. 2005 May;8(5):657-63. PubMed.

View all comments by Michael G. AgadjanyanGSK Vaccines

Since 2005, have other investigators been able to replicate those results from Masliah's group where anti-α-synuclein antibodies are able to penetrate the blood-brain barrier and go into the intracellular compartment (intraneuronal) Lewy bodies to bind α-synuclein?

Since 2005, I have not seen any successful anti-α-synuclein immunotherapy or vaccination except from Sierks's group using ScFV intrabodies.

Experts: Do you believe in that kind of approach for intracellular neurodegenerative deposits?

View all comments by Daniel LarocqueMake a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.